» Enjoy our Liturgical Seasons series of e-books!

Ash Wednesday, the Beginning of Lent:

The time has now come in the Church year for the solemn observance of the great central act of history, the redemption of the human race by our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. In the Roman Rite, the beginning of the forty days of penance is marked with the austere symbol of ashes which is used in today's liturgy. The use of ashes is a survival from an ancient rite according to which converted sinners submitted themselves to canonical penance. The Alleluia and the Gloria are suppressed until Easter.

For members of the Latin Catholic Church, the laws regarding abstinence and fasting are as follows:

- Abstinence from eating meat is to be observed on Ash Wednesday and all Fridays during Lent. This applies to all persons 14 years of age and older.

- Fasting on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday applies to all Catholics who have completed their eighteenth year to the beginning of their sixtieth year. A person is permitted to eat one full meal, as well as two smaller meals that together are not equal to a full meal.

The Memorial of Cyril and Methodius, which is ordinarily celebrated today, is superseded by the Ash Wednesday liturgy.

Station Church Information >>>

Ash Wednesday

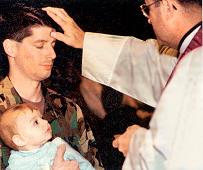

At the beginning of Lent, on Ash Wednesday, ashes are blessed during Mass, after the homily. The blessed ashes are then "imposed" on the faithful as a sign of conversion, penance, fasting and human mortality. The ashes are blessed at least during the first Mass of the day, but they may also be imposed during all the Masses of the day, after the homily, and even outside the time of Mass to meet the needs of the faithful. Priests or deacons normally impart this sacramental, but instituted acolytes, other extraordinary ministers or designated lay people may be delegated to impart ashes, if the bishop judges that this is necessary. The ashes are made from the palms used at the previous Passion Sunday ceremonies.

At the beginning of Lent, on Ash Wednesday, ashes are blessed during Mass, after the homily. The blessed ashes are then "imposed" on the faithful as a sign of conversion, penance, fasting and human mortality. The ashes are blessed at least during the first Mass of the day, but they may also be imposed during all the Masses of the day, after the homily, and even outside the time of Mass to meet the needs of the faithful. Priests or deacons normally impart this sacramental, but instituted acolytes, other extraordinary ministers or designated lay people may be delegated to impart ashes, if the bishop judges that this is necessary. The ashes are made from the palms used at the previous Passion Sunday ceremonies.

—Ceremonies of the Liturgical Year, Msgr. Peter J. Elliott

The act of putting on ashes symbolizes fragility and mortality, and the need to be redeemed by the mercy of God. Far from being a merely external act, the Church has retained the use of ashes to symbolize that attitude of internal penance to which all the baptized are called during Lent.

—Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy

Meditation—An Itinerary of Conversion

The rediscovery of the baptismal character of Lent, the ancient penitential season that precedes Easter, and the restoration of the Paschal Triduum—Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Easter Vigil—as the apex of the Church’s liturgical year are two of the most important accomplishments of modern Catholicism.

Over the centuries, the summit of the Church’s year of grace—the celebration of Christ’s passing over from death to life, for which the Church prepares in Lent—had become encrusted with liturgical barnacles that gradually took center stage in the drama of Holy Week. And while some of them had a beauty of their own, such as the Tenebrae service, celebrated early in the morning of Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, the overall effect was to diminish the liturgical richness of the Triduum; the Easter Vigil’s essential character as a dramatic night-watch, when the Church gathers at the Lord’s tomb to ponder the great events of salvation history while awaiting the bright dawn of the Resurrection, was almost completely obscured. Similarly, Lent, which had an intensely baptismal character centuries ago, became almost exclusively penitential: a matter of what Catholics must not do, rather than a season focused on the heart of the Christian vocation and mission—conversion to Jesus Christ and the deepening of our friendship with him.

Now, thanks to Pope Pius XII’s restoration of the Easter Vigil and the liturgical reforms mandated by the Second Vatican Council, Catholics of the twenty-first century can celebrate both Lent and the Paschal Triduum in the richness of their evangelical and baptismal character, as moments of intensified conversion to Christ and incorporation into his Body, the Church. Lent, once dreaded, has become popular: churches are full on Ash Wednesday, and the disciplines of Lent—fasting, almsgiving, intensified prayer—have now been relocated properly within the great human adventure of continuing conversion. Celebrated with appropriate solemnity, the Paschal Triduum today is what it should be: the apex of the liturgical year, in which those who were initially conformed to Christ in Baptism, along with those baptized at the Easter Vigil, relive the Master’s Passion and Death in order to experience the joy of the Resurrection, the decisive confirmation that God’s purposes in history will be vindicated.

This revival of Lent in the Catholic Church has involved the rediscovery of the Forty Days as a season shaped by the catechumenate: the period of education and formation through which adults who have not yet been baptized are prepared to receive Baptism, Confirmation, and the Holy Eucharist, the three sacraments of Christian initiation, at the Easter Vigil. The baptismal character of Lent is not for catechumens only, however. The adult catechumenate (called the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults) offers an annual reminder to the Church that allalways in need of conversion. The Church’s conversion, the Church’s being-made-holy, is a never-ending process.

Baptism, the Scriptures tell us, is “for the forgiveness of sins.” And while that central aspect of the sacrament is most dramatically manifest in the baptism of adults at the Easter Vigil, those who were baptized in infancy , and who, as all do, inevitably fall into sin, are also in need of forgiveness. Thus baptism “for the forgiveness of sins,” which is such a prominent theme throughout Lent, reminds all the baptized that they, too, require liberation from sin: from the bad habits that enslave us and impede our friendship with Christ.

To make the pilgrimage of Lent is to follow an itinerary of conversion. Lent affords every baptized Christian the opportunity to reenter the catechumenate, to undergo a “second baptism,” and thus to meet once again the mysteries of God’s mercy and love….

The Bible includes three paradigmatic forty-day periods of fasting and prayer: that of Moses, who prepared for forty days to receive to receive the Ten Commandments, the moral code that God gives his chosen people to help them avoid falling back into the habits of slaves [Deuteronomy 9.9]; that of Elijah, who fasted “forty days and forty nights [at] Horeb the mount of God,” prior to hearing the “still, small voice” of the Lord passing by [1 Kings 19:8]; and that of Jesus, prior to his temptation. Thus the “forty days” of Lent—Ash Wednesday through Holy Saturday, exclusive of Sundays (which were always exempted from the Lenten fast as the disciplines of the season became defined)—evoke two great figures from the Hebrew Bible, Moses the lawgiver and Elijah the model of prophecy, as well as the Lord’s own fast in the desert, which is variously described in the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke as the crucial prelude to his public ministry.

In all three biblical instances, these forty days are a stepping-aside from the ordinary rhythms of life in order to be more open to the promptings of the spirit of God, and thus more deeply converted to walking along God’s path through history. That “stepping aside” is a primary characteristic of Lent and, according to the ancient tradition of the Church, is embodied in almsgiving and intensified prayer as well as fasting. The three practices go together. “Giving up _____” for Lent would have little more meaning than a weight-loss program were it not accompanied by a deeper encounter with Father, Son, and Holy Spirit through prayer, spiritual reading, and reflection and a new concern for those in need. Thus the special practices of the Forty Days, like the liturgies of each day of Lent, constantly bring the Christian back to the primordial call of Christ: “Repent, and believe in the Gospel” [Mark 1.15].

—George Weigel, Roman Pilgrimage: The Station Churches

Highlights and Things to Do:

- Go with your family to receive ashes at Mass today. Leave them on your forehead as a witness to your faith. Here is a Lenten reflection on the meaning of the ashes on Ash Wednesday. If you have children, you may want to share this with them in terms that they can understand.

- Today parents should encourage their children to reflect upon what regular penances they will perform throughout this season of Lent. Ideally, each member of the family should choose his own personal penance as well as some good act that he will perform (daily spiritual reading, daily Mass, extra prayers, almsgiving, volunteer work, housecleaning, etc.), and the whole family may wish to give up one thing together (TV, movies, desserts) or do something extra (family rosary, Holy Hour, Lenten Alms Jar).

- Here is a Lenten prayer that the family may pray every night from Ash Wednesday to the first Saturday in Lent, to turn the family's spiritual focus towards this holy season.

- Read Pope Francis's 2025 Message for Lent with the theme: "Let us journey together in hope." Pope Francis likens the penitential season of Lent to our annual pilgrimage of Lent in faith and hope. "The Church, our mother and teacher, invites us to open our hearts to God’s grace, so that we can celebrate with great joy the paschal victory of Christ the Lord over sin and death." As this being a Jubilee Year, we journey together in hope. Our journey is similar to the journey of the people of Israel to the Promised Land. "A first call to conversion thus comes from the realization that all of us are pilgrims in this life; each of us is invited to stop and ask how our lives reflect this fact." We can compare our daily life with that of a migrant or foreigner, "to learn how to sympathize with their experiences and in this way discover what God is asking of us so that we can better advance on our journey to the house of the Father." Journeying together means as Christians we "are called to walk at the side of others, and never as lone travellers." The second call to conversion is to work together in the journey. To journey in hope is the third call of conversion. We are to have "a call to hope, to trust in God and his great promise of eternal life." Again we examine ourselves: "Am I convinced that the Lord forgives my sins? Or do I act as if I can save myself? Do I long for salvation and call upon God’s help to attain it?" We must be sustained in the hope "that does not disappoint.

Station Churches

Roman Stational churches or station churches are the churches that are appointed for special morning and evening services during Lent, Easter and some other important days during the Liturgical Year. This ancient Roman tradition started in order to strengthen the sense of community within the Church in Rome, as this system meant that the Holy Father would visit each part of the city and celebrate Mass with the congregation.

"So vividly was the station saint before the minds of the assembled people that he seemed present in their very midst, spoke and worshiped with them. Therefore the missal still reads, "Statio ad sanctum Paulum," i.e., the service is not merely in the church of St. Paul, but rather in his very presence. In the stational liturgy, then, St. Paul was considered as actually present and acting in his capacity as head and pattern for the worshipers. Yes, even more, the assembled congregation entered into a mystical union with the saint by sharing in his glory and by seeing in him beforehand the Lord's advent in the Mass" (Pius Parsch, The Church's Year of Grace, Vol. 2, p. 71).

For more information, see:

- The Stational Church by Jennifer Gregory Miller

- Roman Pilgrimage: The Station Churches, a review of George Weigel's book by Jennifer Gregory Miller

- Following the Roman Stations by Jennifer Gregory Miller

- A Peek Into Our Daily Roman Station Walk by Jennifer Gregory Miller

- Florence Berger's At Home: Lent and Easter

- The Station Churches of Rome

- Pontifical Academy of the Martyrs: Lenten Stations (Text in Italian)—the Academy has been encouraging the display and veneration of relics at the stational churches.

- The Pontifical North American College: The Roman Station Liturgy—includes commentary for each Stational day.

- Roman Station Churches with Fr. Bill.

- Aleteia: Live Lent with a devotion of the early Christians: Join us to see Rome’s “station churches”

- Station Churches of Rome by Father Coulter

Ash Wednesday:

Station with Santa Sabina all'Aventino (St. Sabina):

The first stational church during Lent is Santa Sabina at the Aventine (Basilica of St. Sabina). It was built in the 5th century, presumably at the site of the original Titulus Sabinae, a church in the home of St. Sabina who had been martyred c. 114. The tituli were the first parish churches in Rome. St. Dominic lived in the adjacent monastery for a period soon before his death in 1221. Among other residents of the monastery were St. Thomas Aquinas.

For more on Santa Sabina all'Aventino, see:

- Churches of Rome Info

- The Station Churches of Rome

- Rome Art Lover

- Roman Churches

- PNAC

- Aleteia

- Station Church by Fr. Coulter

- The Catholic Traveler <

For further information on the Station Churches, see The Stational Church.