Ordinary Time: July 17th

Saturday of the Fifteenth Week in Ordinary Time

Other Commemorations: St. Alexis (RM); Blessed Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne, Virgin and Martyrs (RM) ; Other Titles: Blessed Teresian Martyrs of Compiègne

St. Alexius was an Eastern saint whose veneration was transplanted from the Byzantine empire to Rome, whence it spread rapidly throughout western Christendom. Together with the name and veneration of the Saint, his legend was made known to Rome and the West by means of Latin versions based on the form current in the Byzantine Orient. He was famous for his extraordinary self-denial. Before the reform of the General Roman Calendar today was his feast.

Historically today is the feast of the Blessed Martyrs of Compiegne, sixteen Carmelites who are the first martyrs of the French Revolution that have been recognized. They were guillotined on July 17, 1794 at the Place du Trone Renverse (modern Place de la Nation) in Paris, France.

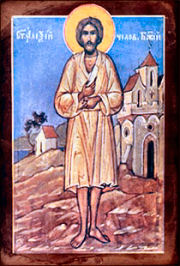

St. Alexis or Alexius

Today, July 17, we celebrate the feast day of Saint Alexis (also known as Saint Alexius, died 404), “Man of God.” Saint Alexis lived in poverty and service to the poor, despite wealthy upbringing and worldly opportunity. His faith and piety was attested to by the Blessed Virgin, who spoke through a holy painting, revealing him to be a “Man of God” to those who regarded him as a beggar. The life of Saint Alexis reminds us that appearances are not what is important to the Lord, but rather the holy fire burning within the heart and soul of the faithful.

Today, July 17, we celebrate the feast day of Saint Alexis (also known as Saint Alexius, died 404), “Man of God.” Saint Alexis lived in poverty and service to the poor, despite wealthy upbringing and worldly opportunity. His faith and piety was attested to by the Blessed Virgin, who spoke through a holy painting, revealing him to be a “Man of God” to those who regarded him as a beggar. The life of Saint Alexis reminds us that appearances are not what is important to the Lord, but rather the holy fire burning within the heart and soul of the faithful.

Alexis was born in Rome, into a holy and pious family. His parents, Euphemianus and Aglais, wealthy and noble, had for some time taken great pity on the poor, and distributed both food and clothing to those in need on a daily basis. From a young age, Alexis imitated his parents, spending hours reading the Holy Scriptures, fasting strictly, distributing alms, and engaging in acts of penance and mortification (such as wearing a hair shirt beneath his fine clothing). He recognized and reported to his parents his calling to serve the Lord, but they had already arranged a marriage to a beautiful and virtuous young woman. Obediently, he agreed to marry, but upon his wedding night, left his bride after giving her his ring and belt, saying, “Keep these things, Beloved, and may the Lord be with us until His grace provides us with something better.”

Alexis disguised himself, leaving his homeland, and sailing East. He arrived in the city of Edessa in Syria, where he sold his remaining belongings (distributing them to the poor) and took up residence beside the Church of the Most Holy Theotokos (Mary, Mother of God). There, he begged for alms, which in turn he bought bread with to feed the aged and infirm. On Sundays he spent the day in the church, receiving the Eucharist, and praying in earnest. His parents sought him everywhere, dispatching servants throughout Europe and the East, but none could find him. Those sent to Edessa could not recognize him without his fine clothing. Plus, he had aged considerably, his body shrunken from fasting, and his former youth and vigor erased by long days and nights of begging. Alexis was thankful, and raised a prayer of thanksgiving to the Lord, that his own servants had given him alms, saying "I thank Thee, O Lord, who hast called me and granted that I should receive for Thy name's sake an alms from my own slaves. Deign to fulfill in me the work Thou hast begun."

Saint Alexis lived in Edessa for seventeen years, during which time Our Blessed Mother revealed his true holiness. One morning, in the church, an icon of the Theotokos spoke to the sacristan as he readied the altar for Mass. She said, “Lead into My church that Man of God, worthy of the Kingdom of Heaven. His prayer rises up to God like fragrant incense, and the Holy Spirit rests upon him.” The sacristan searched, but could not find any many that fit the description of the Holy Mother. Confused and frustrated, he prayed to Mary, begging clarity. Again, a voice from the icon spoke, proclaiming the beggar who sat in the church portico to be the Man of God. The sacristan, despite his misgivings, brought Saint Alexis into the church, and many began to recognize him and praise him thereafter.

Having attracted unwanted attention, and wishing to return to his life of humility and poverty, Alexis left Edessa, boarding a ship for Cilcia, his intended destination the Church of Saint Paul in Tarsus. However, the plan of the Lord is mighty, and a storm forced the ship to dock in Italy. So close to the home of his parents, Alexis traveled by foot to Rome, and took up residence in his own home, beneath the stairs of the grand house he had grown up in. Euphemianus, not recognizing his own son, provided the beggar with a cell in which to live, and ordered that he be given daily rations from the dinner table. Alexis, for his part, lived in humility and prayer, fasting and contemplating the Word of God, enduring the constant jeering and insults at the hands of the servants. He also endured the constant weeping of his wife, whose pain tormented him each day. The only times he left his cell were to attend Mass and teach the local children about the Lord and the faith.

Saint Alexis lived in his family home for seventeen more years, until his death, which the Lord revealed to him in advance. On the day of his death, he took pen and paper, writing a note of apology and begging for forgiveness for the earthly pain he had caused his wife and parents. That day, the day of his death, heavenly voices spoke at Masses offered throughout the city—one to Archbishop Innocent saying, “On Friday morning, the Man of God comes forth from the body. Have him pray for the city, that you may remain untroubled.” Those present were terrified, falling to the ground upon hearing the heavenly voice. Upon recovering, they searched the city, but were unable to locate humble Alexis, living under the stairs in his father’s courtyard. A second voice was heard by the Pope, while serving Mass in the Church of Saint Peter. The voice spoke, “Seek the Man of God in the house of Euphemianus.” Many traveled to the house, including the Pope and Emperor, but Alexis was found to be dead. His face was transformed into that of a angel, his youth and vigor restored and enhanced. In his hand, he clasped his final note, but it was unable to be pried free until the Pope and Emperor—addressing him as if he were alive—asked to read it.

Upon hearing the request, the hand of Alexis opened, and the letter was read. His wife and parents tearfully venerated his body, praising the Lord for returning their lost son and husband to them, and for giving him the strength of will to live a life of penance from the day of his marriage to the day of his death. Carried by the Pope and Emperor, the body of Saint Alexis was displayed for the citizens of Rome to venerate, and then interred in a marble crypt within the Church of Saint Boniface. Many miracles were reported at his tomb side, and a sweet myrrh was noted to flow from the crypt, healing the sick.

The life of Saint Alexis is one of humility and obedience. This Man of God is also remarkable for his daily struggle against the vice of pride. On many occasions—while enduring the jeers of his servants, while starving, while becoming invisible to society—Alexis could have asserted his position by stating his identity, embracing his pride and putting aside his penance and suffering. Rather, he asserted his love for the Lord, himself diminishing. We all struggle with pride, in this modern age. We are judged by others by our worldly accomplishments, wealth, status, position, successes—all of which foster a sense of individual responsibility for the course of our lives. We might look to Saint Alexis on this, his feast day, as a reminder that all we have—all we are graced with—is given to us by Our Heavenly Father. We do not achieve, rather we accept. And in that acceptance, we recognize our weakness. We recognize that we are undeserving. And we give thanks and praise to the Lord for allowing us to “succeed”—not for our personal glory, but for His.

Patronage: Alexians; beggars; belt makers; nurses; pilgrims; travellers

Symbols and Representation: A beggar or pilgrim holding a staircase (his emblem); asleep by the stairs; dirty water emptied on him; as a pilgrim with a staff and scrip; as a pilgrim; kneeling before the pope, to whom he gives a letter; dying man with a letter in his hand; man holding a ladder; man in a pilgrim‘s habit holding a staff; man lying beneath a staircase; man lying on a mat; old and very ragged beggar with a dish; dish; old man dressed as a pilgrim; cross; palm (his sufferings and patience led some to consider him a martyr)

Highlights and Things to Do:

- Today would be a good time to reflect on poverty of spirit. We have brought nothing into the world, neither can we take anything out. Having food and clothing, let us be content. Those who wish to become rich will fall into temptation and into the snares of the devil because the love of money is the root of all evil. How powerful these words sound coming from the lips of St. Alexius, for he actually lived them in all their bitter implications. He left all and followed the Lord. Examine yourself on how detached you are from material things. Offer your rosary or a prayer that you will have the grace to be poor in spirit.

- Learn more about St. Alexis:

The Blessed Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne

On July 17, 1794, sixteen Carmelites caught up in the French Revolution were guillotined at the Place du Trône Renversé (now called Place de la Nation), in Paris.

On July 17, 1794, sixteen Carmelites caught up in the French Revolution were guillotined at the Place du Trône Renversé (now called Place de la Nation), in Paris.

When the revolution started in 1789, a group of twenty-one discalced Carmelites lived in a monastery in Compiegne France, founded in 1641. The monastery was ordered closed in 1790 by the Revolutionary government, and the nuns were disbanded. Sixteen of the nuns were accused of living in a religious community in 1794. They were arrested on June 22 and imprisoned in a Visitation convent in Compiegne There they openly resumed their religious life.

For a full twenty months before their execution, the sisters came together in an act of consecration “whereby each member of the community would join with the others in offering herself daily to God, soul and body in holocaust to restore peace to France and to her Church.”

The nuns were not just mere victims of the Revolution overcome by circumstances. Each contemplated her martyrdom; each understood her offering. Each sought that “greater love” of giving herself for her fellow man in imitation of the Divine Lamb Who redeemed humanity.

On July 12, 1794, the Carmelites were taken to Paris and five days later were sentenced to death. Before their execution they knelt and chanted the "Veni Creator", as at a profession, after which they all renewed aloud their baptismal and religious vows. They went to the guillotine singing the Salve Regina. They were beatified in 1906 by Pope St. Pius X.

The Carmelites were: Marie Claude Brard; Madeleine Brideau, the subprior; Maire Croissy, grandniece of Colbert Marie Dufour; Marie Hanisset; Marie Meunier, a novice; Rose de Neufville Annette Pebras; Anne Piedcourt: Madeleine Lidoine, the prioress; Angelique Roussel; Catherine Soiron and Therese Soiron, both extern sisters, natives of Compiegne and blood sisters: Anne Mary Thouret; Marie Trezelle; and Eliza beth Verolot. The martyrdom of the nuns was immortalized by the composer Francois Poulenc in his famous opera Dialogues des Carmelites.

—Excerpted from Catholic Fire

Highlights and Things to Do:

- You can learn more about the Carmelite Martyrs in Gertrud von le Fort's historical novel, Song at the Scaffold; William Bush's "To Quell the Terror, or go here and read Terrye Newkirk's excellent essay.

- Find out more about the Sixteen Martyrs:

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- Wikipedia

- CNA

- The Six Bells for more information.

- Listen to the Catholic Culture Podcast 152—The most Catholic opera: Dialogues of the Carmelites w/ Robert Reilly, an interview with author and music critic Robert Reilly.

- On February 22, 2022, Pope Francis opens special process to canonize 16 Carmelite martyrs of the French Revolution, by which they could be canonized as saints without recognition of a miracle attributed to their intercession.