The King's Good Servant: Living the Faith in the Church and in the World

by Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap.

A married friend of mine says that his palms start to sweat whenever his wife says, "Sweetheart, do you love me?" The reason is simple. It usually means that very soon he'll be proving it with another new project around the house.

Relationships have consequences. In a loving marriage or a good friendship, the rewards are always much greater than the work. But it's true that if we love somebody, then we appropriately submit ourselves to their needs. We put them first. We conform our actions to their good expectations. Their life becomes our life.

Certain behaviors follow. We don't cheat on persons we love. We don't ignore what they say. We don't lie and promise that we'll do something — but then do something else. We don't criticize them to outsiders. We don't undermine them with other family members or friends.

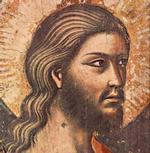

Now, just as it is in marriages and friendships, so it is for disciples with Christ and His Church. When Jesus asked, "Simon, son of John, do you love me?" (Jn 21:17), He had a reason. As soon as Peter answered yes, Jesus said, "Then feed my sheep." Relationships have consequences. If we really love Jesus Christ, then we'll also love His Church. If we really love Jesus Christ, then our actions will prove it. What we really love and believe, we act on. And what we don't act on, we don't really love and believe.

As American Catholics, we too often confuse our faith with theology, or ethics, or pious practice, or compassionate feelings. All of these things are important, but none of them can substitute for the command we received in the First Letter of Peter: "[A]s he who called you is holy, be holy yourselves in all your conduct" (1:15).

Holiness means being in the world but not of it. It means being different from and other than the ways of our time and place and political parties, and conformed to the ways of God:

"For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, says the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my thoughts than your thoughts" (Is 55:8,9).

Living our faith sets Catholics apart. Discipleship has a cost. To the degree Catholics have longed to join the American mainstream — to the point of becoming like everyone else, accommodating to the world and being assimilated rather than witnessing and converting — we've abandoned who we really are. We've forgotten our purpose as a holy people. And we'll only recover our identity when we change; when we center our lives in God. We need to become holy ourselves — in our private choices, in our shared life in the Church and also in our public actions.

My topic tonight is "living the faith," and I want to focus first on what that means for our life as the Church, because this is a Catholic campus, and I'm a Catholic bishop, and we're talking about issues that affect Catholics in living their Catholic convictions. I'm sure we have non-Catholics in the audience, and I'm very grateful and happy that you're here. But my remarks tonight are meant especially for those of us who are Catholic.

I write a lot of letters every day because a lot of people write to me, and my parents always taught me that ignoring anyone is bad manners. So I always write back. That means I have a lot of interesting pen pals. Some are happy, some are angry, and a few are a little strange. One of the angry ones emailed me some time ago to complain that the Archdiocese of Denver was becoming a magnet for every flaky, right wing new group in the Church. And I immediately thought: Thank you, God, for a great way to sneak St. Francis into my talk.

It’s true that God has raised up many new communities in the Church over the last 60 years, especially since Vatican II. It’s true that all of them have weaknesses along with their strengths. And it’s also true that the Archdiocese of Denver has welcomed them with an openness they don't always find elsewhere. I think that’s partly because of the vision of my predecessor, Cardinal Francis Stafford, and partly because of the conversion our own local Church underwent with World Youth Day 1993.

But in each of the new groups that has taken root in Colorado – groups like the Community of the Beatitudes, the Neocatechumenal Way, the Christian Life Movement, the Fellowship of Catholic University Students, the charismatic renewal, Opus Dei, Cursillo, the Marian Community of Reconciliation, Families of Nazareth, the Sodalitium Christianae Vitae – in all of these cases, their spirit is very familiar to anyone who knows St. Francis of Assisi.

Francis once said that, “the saints lived lives of heroic virtue, [but] we are satisfied to talk about them.” Francis was never satisfied with pious words. He wanted to act on the things he believed. He saw that the Gospel wasn’t complicated, but it was demanding and uncomfortable. And that didn't fill him with fear. It energized him.

Francis lived in a time just as difficult as our own. It was an age of Christians killing Christians, Muslims and Christians killing each other, wars between cities and states, and corruption both within and outside the Church. Society and the Church were changing. The feudal system was falling apart. For much of his life, Francis was lost in that confusion. But in his faith and prayer, he came to some basic insights that gave him a powerful inner freedom.

What Francis discovered was simple. He experienced God as a loving Father — and knowing that a father doesn't give his son a scorpion when he asks for bread, Francis decided to live in the world as God’s child. He began to graft his own life onto the way of Jesus Christ.

Right away that had consequences. Because of his love for God as his Father and Jesus as his Brother, Francis began to see other people in a new way. They became his sisters and brothers because they were sons and daughters of God, and sisters and brothers of Jesus Christ — and that relationship wasn’t just words. It was real. Everyone and all creation that flows from the Fatherhood of God are somehow “children” of God. Francis’ ability to seek real holiness and to be a poor man came directly from this understanding of God’s personal love. He wanted to depend on nothing but the providential love of God, his Father.

That peace Francis experienced is something all of us need to consider carefully today, because many of us are probably worried about the Church. We have all sorts of factions arguing within her ranks. Francis faced many of the same problems. And yet a key part of his spiritual life was his love for the Church, his obedience to her pastors, and his unwillingness to be critical of the Church. Instead of tearing her down because of the sins of her leaders, Francis chose to love the Church and serve her — and because of that love and by his simple living of the Gospel without compromise, he became God's agent in renewing a whole age of faith.

Tradition tells us that when Francis met with his community he would often say to them, “Brothers, up to now we have done nothing. So let us begin.” And I think that even though we’ve accomplished many good things in the Church in the United States, even though we have hundreds of new buildings, 19,000 parishes and tens of thousands of people doing religious education and evangelization, teaching in our schools, running our charities, teaching in our universities, doing RCIA and taking part in the Liturgy — despite all these things, if we really want to be what God calls us to be, we need to be like St. Francis.

We need to say to each other every day, “Brothers and sisters: Up to now we’ve done nothing — but let’s begin." Let’s begin to live as if our Baptism matters. Let's begin to live as leaven in the world. Let's begin to act like the missionaries Christ called us to be when He told us to "go, make disciples of all nations."

Francis wasn’t the only Church reformer of his day. Plenty of other men and women saw the problems in the Church and tried to do something about them. Francis wasn’t even the smartest or the most talented – but he was certainly one of the most faithful, most honest, most humble, most single-minded in his mission, and one of the most zealous in his love for Jesus Christ. I’d argue that these marks of authentic Church renewal haven’t really changed at all in 800 years. And that’s why, as a Capuchin Franciscan, I see the spirit of St. Francis in so many of the new movements and communities taking root in the Church.

Whenever I hear people talking about the need for Church reform, the first thing I ask is how they feel about obedience. Francis of Assisi was a strong, shrewd man, and he was nobody’s fool — but both he and St. Clare insisted on being obedient to the Church and her pastors because Jesus was obedient to His Father, and they understood that our salvation comes through that submission of obedience.

Francis understood what Vatican II reaffirmed: that the Catholic Church is the universal sacrament of salvation, and no distinction can be drawn between the institutional Church and the “real” Church – they are one and the same (LG 1;8). Blessed John XXIII said that the Catholic Church is the soul of the world, the "mother and teacher of all nations... the ‘pillar and the ground of truth'... entrusted by her holy founder [with] the twofold task of giving life to her children, and of teaching them and guiding them – both as individuals and as nations... ” (Mater et Magistra, 1).

And yet most us treat the Church the same way we treat our flesh and blood mothers. We want the mother part, but we don’t want the teacher part. We want her around to feed us, encourage us and offer us solace when things are going badly. But we don’t want her advice, especially when it interferes with our comfort.

A very great Jesuit once said that “If we wish to proceed securely in all things, we must hold fast to the following principle: What seems to me white, I will believe black if the hierarchical Church so defines. For I must be convinced that in Christ our Lord, the Bridegroom, and in His spouse, the Church, only one Spirit holds sway, which governs and rules for the salvation of souls. For it is by the same Spirit and Lord who gave the Ten Commandments, that our holy mother Church is ruled and governed.”

Those are the words of Ignatius Loyola. They sound pretty unsettling to the American ear. But like St. Francis, St. Ignatius lived in a time just as conflicted as our own. He was certainly no fool about the defects of human nature and leadership; or about what the Church needed in order to renew her mission to the world. But he understood that the Catholic Church really is the bride of Christ, and our mother and teacher. He understood that we find our deepest freedom in obedience to the truth and in service to God's will – exactly as Jesus showed us in the example of His own life.

When an individual or even a religious community redefines obedience to mean something other than a practical, willing obedience to the Gospel and to the pastors of Christ’s Church – no matter how imperfect those pastors are — what always results, without exception, is disobedience to Christ Himself. So if the new communities in the Church are “right wing and flaky” because they seek to be obedient, then so was St. Francis, and we need a lot more of it.

If the new communities in the Church are “right wing and flaky” because they preach Jesus Christ without caveats or excuses, and they want to bring the whole world to believe in Him, then so was St. Francis, and we need a lot more of it.

If the new communities in the Church are “right wing and flaky” because they choose joy and zeal and hope rather than fighting for what they mistake to be power; or because they’re more interested in actually living the Catholic faith than in reshaping it in the image of their own theology, then so was St. Francis, and we need a lot more of it.

Does that mean we all need to run out and join a renewal movement? No. Of course not. Most of us belong right where we are, in our parishes. But it does mean that we need to rediscover who we are by learning from their witness. Catholics are a missionary people. We need to be Catholics first. Everything else is secondary. We're not here to make a deal with the world. Were here to convert it.

It’s always easier to talk about reform when the target of reform is “out there,” rather than in here. The Church does need reform. She always needs reform, which means she needs scholars and liturgists and committed laypeople to help guide her, and pastors who know how to lead with courage and love. But what she needs more than anything else is holiness – holy priests and holy people who love Jesus Christ and love His Church more than they love their own ideas or even their own political parties.

Exactly like 800 years ago, the structures of the Church are so much easier to tinker with than our own stubborn heart, or that big, empty hole where our faith should be. Make no mistake. The root problem in the Church today isn't a crisis of organization or even of sinful behavior, as terrible as that can be. The root problem is an issue of faith — and the lack of it. We can't give what we don't have. Too many of us claim to believe, but then we act like we don't. Too many very decent people pray the Nicene Creed every Sunday without really considering what it means for their lives. If we really mean it when we say, "I believe in one, holy, Catholic and apostolic Church," then how can we ignore her when she teaches in the name of Jesus Christ on issues like the sanctity of human life?

Reforming the Church, renewing the Church, begins with our own repentance and conversion, our own submission to God's will, our own humility and willingness to serve — and that’s the really hard work, which is why so little of it seems to get done.

Now let's turn to what living the faith means for our life in the world.

If we’re serious about our faith, then our whole lives should be formed and guided by our Catholic convictions. All of our actions and all of our choices should be rooted in our Catholic identity and in our relationship with God. That means our choices at work; at play; within our families; and also the choices we make in the exercise of our citizenship.

Citizenship is an act of social responsibility and political power in the presence of God. And when we step into the voting booth, we either help to build His civilization of love... or its opposite.

For Catholics, the job of good citizenship is a subset of Catholic social doctrine. If we want to know Catholic social doctrine in a nutshell, just read Mark 12:29-31. A scribe asks Jesus, “Which commandment is the first of all?” And Jesus answers:

“... ‘Hear O Israel, the Lord your God, the Lord is one; and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength. The second is this: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.”

Jesus is reciting the shema, quoting directly from Deuteronomy and Leviticus. A Jewish man would repeat the shema – “Hear O Israel, the Lord your God, the Lord is one” – many times a day. He would do it to ground himself in the truth that God, and only God, is the center of everything. Nothing should compete with God. When we forget God, everything else starts to unravel.

In other words, the love and justice we owe our neighbor is rooted in the love and obedience we owe to God. The rights of other people come from the fact that we’re all created by the same Father. We’re all made in His image. God owns life. We don’t. That’s why the first principle of loving our neighbors is: Don’t kill them. That’s why, in understanding the Ten Commandments, we should observe that the first three commandments govern our fundamental relationship with God — and only because of them can the other seven commandments govern our relationships with each other.

What’s this got to do with Election 2004? Actually, quite a lot. And here’s why. God guarantees the “humanity” of human society. All political authority derives its legitimacy from God’s authority – and therefore is accountable to Him. Without God, human authority very quickly becomes inhumane. We can see this happening in our own country today. That’s why the Church always has a lot to say about culture, economics, politics and social justice. That’s part of her missionary mandate, and also ours. The witness of the Church on “social issues” begins in Scripture, runs through history in the papal encyclicals and the Second Vatican Council, and continues today in documents from the U.S. bishops like Living the Gospel of Life and Faithful Citizenship.

Here’s an example that applies directly to our discussion tonight. Forty-one years ago (1963), Pope John XXIII wrote an encyclical letter on world peace called Pacem in Terris. But he didn’t begin it by talking about the arms race or international relations. He began it by talking about the rights and duties of the individual human person — and justice between individuals, and within societies.

Why did he begin that way? It’s because the “big picture” depends on the “small picture.” World peace begins with a respect for the dignity of the individual human person. That's why Mother Teresa always said that abortion is the seed of war. John XXIII wrote that “every human being is a person” (9). And he said that “every man has a right to life, to bodily integrity, and to the means which are suitable to the proper development of life; these are primarily food, clothing, shelter, rest, medical care, and finally the necessary social services” (11).

The big picture depends on the small picture. No amount of good policy on immigration, or unemployment, or education, or housing, compensates for bad policy when it comes to deliberately killing the innocent — beginning with the unborn. The right to life comes first. That’s the priority. It’s the foundation of every other right. Without it, every other right is built on sand.

Of course, if the “right to life” is the only issue Catholics care about, that doesn’t work either. In Genesis 9:5, God says, “From man in regard to his fellow man I will demand an accounting.” The Epistle of James 2:15-17 says that:

“If a brother or sister is ill-clad and in lack of daily food, and one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace, be warmed and filled,’ without giving them the things needed for the body, what does it profit? So faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead.”

Faith without works is dead. We need to act on what we claim to believe. Vatican II teaches that “the political community exists... for the common good [which] embraces the sum total of all those conditions of social life which enable individuals, families and organizations to achieve complete and efficacious fulfillment” (GS, 74). It also teaches that, “Every citizen ought to be mindful of his right and his duty to promote the common good by using his vote.” (GS, 75).

Catholics have the right and the obligation to demand that their public officials — and their public policies – should promote the common good. Public officials should protect marriage and encourage family life; they should help the poor and homeless; they should promote economic justice both at home and abroad; and they should support the sick, the elderly, and children seeking a decent education.

It’s not enough to say, “Well, these are matters for private charity.” Private charities in this country are already overwhelmed by the demand. For Catholics, it’s completely proper for government to be involved in a serious way in solving these problems – as long as the so-called “solutions” don’t promote or allow killing the unborn and the weak.

As Catholics we have a duty to vote. That means we also have a duty to know what the candidates stand for — and what the Catholic faith teaches. And we can't assume that newspapers and the television will give us the information we need. Neil Postman once said that the main contribution TV has made to the American political process is this: A short, fat, ugly person cannot be elected president – even if he has the genius of Einstein and the sanctity of Mother Teresa.

We have the obligation to know what the Church teaches. At a minimum this year, that means we should read and study the U.S. bishops' 1998 pastoral letter, Living the Gospel of Life. It's the one election year document that everyone in this room should know. And then, in the light of Living the Gospel of Life — and never apart from it — we should read and reflect on Faithful Citizenship.

We also have the duty to vote our conscience. But remember that for Catholics, conscience is never just a matter of private opinion or personal preference. As Cardinal George says, feeling really sincere or really regretful about doing an evil thing doesn't make it right. Vatican II reminds us that “in forming their consciences, the faithful must pay careful attention to the sacred and certain teaching of the Church. For the Catholic Church is by the will of Christ the teacher of truth” (DH, 14). If our private conscience conflicts with the Church — especially on an important teaching — the problem is probably not with the Church. It’s much more likely with our conscience.

Every election, including the one this November, is a tale of two virtues: prudence and courage.

Prudence is the right rudder of reason, the virtue that helps us judge what we should do in any particular circumstance to achieve good and avoid evil.

In politics, prudence seeks the common good by weighing alternatives, making reasonable compromises and avoiding unnecessary conflict. Not every campaign issue is life and death, and no candidate is perfect. Good people can often choose to vote for very different political courses.

Prudence also shows us which compromises can be made, and which can’t; which conflicts can be avoided, and which really do need to be engaged. The abortion issue cannot be avoided. It's the central moral conflict of this moment in our nation's history. Every abortion kills an unborn child. Every abortion leaves a woman emotionally scarred. Every abortion is a grave act of violence. All of these things fundamentally damage the common good.

We also need to remember that pro-abortion activists have been attacking the freedom of conscience of Catholic and other health-care providers for years. We’re long past the point when so-called “pro-choicers” talked about the tragedy of abortion and the need to make it safe and rare. The abortion lobby now wants abortion available anywhere, anytime, for any reason, and preferably for free. And they don’t care who they bully or coerce, or what basic rights they violate to get it.

Every election year I hear from Catholic voters looking for a way to evade or “contextualize” the abortion issue. Some complain that the Church is imposing her views on society at large. Others argue that they personally oppose abortion, but that it should be sheltered as a matter of private choice. Others want to minimize the gravity of abortion by weighing it against a dozen other social issues.

None of these arguments finally has merit.

First, democracy depends on good people working vigorously for their convictions in the political arena. Abortion is the worst kind of intimate violence. Being quiet about it in our politics out of a misguided sense of “good manners” is the worst kind of callousness, and the worst kind of bad citizenship.

Second, if we choose to allow deliberate attacks against the innocent, we can’t wash our hands of the consequences of that violence. No violence is ever private. That includes abortion. If we choose to allow it, we choose to own it.

Third, the "seamless garment" doesn't mean and never meant that all social issues are equal. The hierarchy of truths in the Catholic faith does not mean that some truths are "more true" than others. It does mean that some issues have priority, and some don't. Abortion is separated from other important social issues like a just wage, affordable housing, and even the debate over the war in Iraq, by a difference in kind, not a difference in degree. Every abortion deliberately kills an innocent, unborn human life — every time. No matter what kind of mental gymnastics we use, elective killing has no excuse. We only implicate ourselves by trying to invent one.

Jesus told His disciples to render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s. Not many things actually belong to Caesar. And our souls very clearly belong to God – not to Caesar. As Catholics, our relationship with the surrounding political order will always involve a process of reflection and judgment. Our debates about politics and policies are always questions of faith.

Every election is a tale of two virtues: prudence and courage. Courage is the bravery to do what's right in the light of our faith, even if we fear the consequences. Without courage, prudence very quickly becomes an alibi for cowardice.

We could all use a little more courage this election year. If we’re really Catholic, we need to act like it. We get the elected officials we deserve, and — speaking only for myself — I’m not willing to accept the hypocrisy of “pro-choice” political reasoning and the abortion lobby that supports it.

Personally, I will vote for no candidate – Republican, Democrat or third party — who is actively “pro-choice.” Congress deserves better than that. So does Colorado. So does our nation.

In living our faith and in living our citizenship, we need to begin with the end in mind. Where do we want to spend eternity? Because we won't spend it here. We're citizens of God's kingdom first. That's our homeland. That's the citizenship we need to be faithful to, because if we serve God well, we serve our nation well. If we live as faithful Catholics, we live as faithful Americans.

But if we try to separate our Catholic convictions from the political and other decisions we make, then we're no better than thieves — because we steal from American public life the most important gift we have to offer: the truth of Jesus Christ and the wisdom of His Church.

St. Thomas More, who knew exactly what he did and didn't owe to Caesar, said "I am the king's good servant, but God's first. " I think he had his priorities right. We should follow his lead.

This item 6198 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org