Charles Borromeo and Catholic Tradition Regarding the Design of Catholic Churches

While the Tridentine documents contained few specific directives regarding the design of Catholic churches in the context of the Protestant Reformation, the Council affirmed the authority of tradition in all matters related to Christianity. It was in that context that one of the main participants in the Council wrote a summation of the Church's tradition regarding the design of Catholic churches. In light of the two most recent documents regarding the design of Catholic churches in the United States, Environment and Art in Catholic Worship (1978) and Built of Living Stones: Art, Architecture, and Worship (2000), it is useful to revisit the understanding of Church tradition that existed prior to their publication.1

Charles Borromeo (1538-1584), whom the Catholic Church recognizes as a saint, published a summary of Catholic traditions regarding church design fourteen years after the conclusion of the Council of Trent. Borromeo's publication, Instructiones Fabricae et Supellectilis Ecclesiasticae, was the central document that applied the decrees of the Council of Trent to the design and furnishing of Catholic churches.2 Borromeo officially wrote the Instructiones to direct construction within the Archdiocese of Milan, but his intention was that it have wider usage. Borromeo published the document in 1577, and it was reprinted without major revisions at least nineteen times between 1577 and 1952. Until the late 1960s the architecture and furnishings of most Catholic churches throughout the world were consistent with the Instructiones' directives.

Borromeo began his treatise with a letter in which he identified that he was compiling the directives from information provided by two sources of authority, one ecclesiastical and the other secular. He wrote:

. . . this only has been our principle, that we have shown that the norm and form of building, ornamentation and ecclesiastical furnishing are precise and in agreement with the thinking of the Fathers . . . and . . . we believe it necessary to take the advice of competent architects.3

As an active and influential participant in the Council of Trent, Borromeo had intimate knowledge of the Church's official decrees and of their intent.4 He served as the Papal Secretary of State under Pope Pius IV during the Council's final sessions. He also was one of the most influential agents of reform after the Council's conclusion, serving first as the Papal Legate to Italy and then as the Archbishop of Milan. Along with authoring Instructiones, he exerted great influence in the writing of the Church's revised ceremonial manual, Pontificales secundum ritum et usum Sancte Romane Ecclesia (1561); the decree regarding priest's seminary training, Cum adolescentium aetas (1563); the revised Roman Breviary (1568); and the revised Roman Missal (1570).

Borromeo's Instructiones incorporated his awareness of Catholic church architecture in Italy as well as of Church teaching and of recent and historic Church and secular documents. There is evidence that Borromeo owned a copy of and incorporated ideas from a sixteenth-century edition of the medieval text by William Durandus, Rationale Divinorum Officiorum (c. 1280), which deals with the symbolism of churches and church ornament.5 Evidence of Borromeo's reliance on Durandus' text in the Instructiones, is his consistent use of numbers that correspond to Catholic doctrinal teachings as Durandus recommended. These include use of the numbers three, five, seven, and twelve in recognition of respectively the Trinity, Pentecost, the Seven Sacraments, and the Twelve Apostles.

Borromeo's Instructiones also incorporate ideas that were contained in secular architectural treatises to which he had access.6 These included the ancient Roman treatise by Vitruvius, De Architectura (c. 49 BC – 14 AD); Pietro Cateneo's L'Architettura di Pietro Cateneo Senese (1554); and Andrea Palladio's I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura (1570). These secular sources as well as Church tradition advocated using platonic forms such as circles, domes and vaults as evocations of perfection and of the heavenly realm. Both Church and Western aesthetic tradition favored the use of an odd rather than of an even number of units so that a composition would always have a clear center. This predilection for centrality and anthropomorphism often resulted in symmetric compositions. If circumstances dictated asymmetry, the right side was favored due to the negative associations within Western civilization of all things related to the left, including the Latin word for left, sinestra.

From this wide range of ecclesiastical and secular sources Borromeo compiled neither a theoretical nor a theological work, but a compilation of the Church's traditional design elements and organizational strategies for Catholic churches. It was Borromeo's goal to design elements that conformed to official Church teaching and not to advocate a particular aesthetic style. While this is true, Borromeo wrote the Instructiones in the context of the explosion of artistic creativity which typified the baroque aesthetic. The Counter Reformation and the baroque aesthetic were symbolic. While the Catholic Church was emphasizing that the sacred could be encountered through the senses and most Protestant reformers were rejecting this idea, architects, sculptors, and artists such as Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini, who were working for Catholic clients, were developing the baroque aesthetic. These designers worked with the intention of integrating all the visual arts to maximize the engagement of people's sensibilities. Despite the boisterous aesthetic context in which Borromeo was writing, he only occasionally refers to the classical orders or other stylistic issues within the Instructiones.

Borromeo organized the text of the Instructiones into thirty-three chapters. Thirty chapters focus on the design of typical parish churches, and also include information regarding cathedrals. The last three chapters address the design of churches for oratories, convents, and monasteries. Despite the chapters' titles, the topics covered are not always clearly segregated within the chapter divisions. The first thirty chapters address six categories of information: a church's siting, plan configuration, exterior design, interior organization, furnishings, and decoration.

With regard to a church's siting, Borromeo states that a church should be in a prominent location.7 If natural topography does not provide an advantageous site to give a church visual prominence as well as to guard against floods and dampness, the church should be placed on a raised platform. Borromeo recommends that three or five steps provide access to the platform. If circumstances require that there be a greater number of steps, there should be a landing at either every third or fifth step. Churches are to be freestanding, having no structures directly attached to them other than a sacristy. The residence of the pastor or bishop may be close by or connected to the church by a passage, but the church and clerics' residence should not share a common wall. Churches should be situated in non-commercial areas, far from stables, markets, noise, unpleasant smells, or taverns. If possible, a church's sanctuary should be toward the east and should align with the sunrise at the time of the equinox.

Borromeo's concerns regarding the siting of churches are consistent with those contained within the architectural sources with which Borromeo was familiar. Palladio, one of those sources, states that churches should sit on prominent sites within a city or on public streets or next to a river so that people passing through a town may see them and:

may make their salutations and reverences before the front of the temple [church].8

Catholics frequently observed this custom by making the sign of the cross, whenever thy walked or drove past a church, and men customarily tipped their hats. Borromeo's siting directives are also consistent with the hierarchy of building types as they were understood in Western civilization from the Renaissance era until the nineteenth century.9 Renaissance architectural theorists recognized that there are five building types to which all buildings conform and among which a hierarchy of status exists. Places of veneration, such as a domus dei, hold the most exalted place within that hierarchy and as such require prominent siting, the expenditure of superior craftsmanship and materials, and should be freestanding. Buildings of lesser importance such as private residences, commercial structures, or markets merit less prestigious sites, and more modest expenditures of material, labor, and financial resources.

Borromeo clearly states that the Latin cross or cruciform plan is the preferred configuration for Catholic churches.10 He does recognize that central plan configurations also have historical precedent, and siting, economic concerns, or other circumstances may require variations from the Latin cross prototype. Not distinguishing between the terms "nave" and "aisle," Borromeo states that a church may have one, three, or five "naves," meaning that the church may be a hall church, or have either single or double aisles on either side of its nave. A church's main entrance and nave should align axially with the church's main sanctuary. The sanctuary, if possible, should be contained within a vaulted apse form.

Borromeo indicates that there should be a distinct architectural element that forms the entrance into a church. Dependent on site and budget restraints, an atrium, portico, or vestibule, or a combination of these elements can fulfill this requirement. This component of a church's façade regardless of its form should have a distinguishable depth and serve as a visible transition space into the church. At various times in history, this transition space accommodated ritual initiation into the church or ritual cleansing. Borromeo appears to reject this transitional space's cleansing associations. He stipulates that the holy water vase that contains the blessed water with which members of the congregation cross themselves upon entering a church, be located not in the transitional space, but inside the church itself.

Borromeo suggests that a church should be large enough to accommodate not only the area's local inhabitants, but also the large numbers who would congregate from distant places for holy days. He identifies that a church's interior area should provide approximately four square feet of space for each person who will attend the church regularly.

Seven different chapters in the Instructiones address aspects of the exterior appearance of a Catholic church. Borromeo identifies that the church's entrance façade is its most important exterior wall and that it should contain all of a church's exterior ornamentation and decoration. Narrative visual embellishments normally should not be placed on a church's side or rear elevations. In reference to the nature of the front façade's narrative decoration Borromeo writes:

— there is one feature above all that should be observed in the façade of every church. In the upper part of the chief doorway on the outside, there should be . . . the image of the most Blessed Virgin Mary, holding her son Jesus in her arms; on the right-hand side there should be the effigy of the saint to whom the church is dedicated, while on the left-hand side . . . the effigy of another saint to whom the people of that parish are particularly devoted.

Borromeo recognizes that if circumstances do not allow having three separate images or statues on a church's front façade, then at least the image of the saint to whom the church is dedicated should be represented.

Borromeo's directives regarding a church's exterior doors and windows had both practical and symbolic purposes. He states that a church's front façade should have an odd number of doors, and if possible reflect the church's number of "naves" [nave and aisles]. If a church's central nave is sufficiently wide, three doors should enter directly into the nave in addition to single doors that lead into the nave's adjacent aisles. Borromeo observed that if a church does not have side aisles, it still should have three doors in its front façade. A church therefore should have a total of three, five or seven doors in its front façade. The central doorway should be the largest and have greater ornamentation, especially if the church is a cathedral, as it accommodates the clergy and their retinue in ceremonial processions. Borromeo's directives regarding the location of windows are equally specific. His concerns relate to issues of illumination, security, and maintaining a proper decorum within a church. He writes:

the windows should be constructed as high as possible, and in such a way that a person standing outside cannot look inside.

If possible a church's principle source of interior illumination should be provided by clerestory windows into the church's nave and windows that are placed high on the walls of the church's side aisles. All windows should have provisions to guard against unauthorized entry and should be odd in number. If the church has a nave and aisle configuration, the window spacing should align with the center of the spaces that are defined by the columns in the nave arcade or colonnade. If the nave requires additional illumination, a window, preferably round, should be placed above the doorways in the church's front façade or in the walls of its apse. Borromeo observes that lanterns that project above a church's roof line and oculi in domes can illuminate either a church's sanctuary or nave from above, but cautions that such devices are difficult to make watertight. Borromeo is adamant about not placing altars directly under or close to a potential source of water leakage. He also discourages placement of windows in any location where the illumination provided by them would prevent the congregation from having a clear view of either the main altar or side altars.

Borromeo's directives regarding windows closely follow those of the Renaissance architectural theoretician and Catholic priest Leon Battista Alberti. Alberti stated that:

nothing but the sky may be seen through them [the windows], to the intent that both the priests that are employed in the performance of Divine Offices, and those that assist on account of devotion, may not have their minds in any way diverted.11

Church tradition as expressed by Durandus held that:

. . . by the windows, the senses are signified: which ought to be shut to the vanities of this world, and open to receive with all freedom spiritual gifts.12

Bells and bell towers are the last exterior features of a church that Borromeo addresses.13 He states that the purpose of church bells is to call people to liturgy within the church, to mark the hours at which the Divine Office is to be prayed, to mark the times of the Angelus, and to toll the death of one of the faithful. He instructs that bells should be either in a freestanding tower, or in towers that form a part of the church's front façade. If there is only one tower, it should be on the church façade's right side as a person approaches the church. If circumstances do not permit the construction of a bell tower, the bell may hang within a pier or buttress in the same location as that of a single tower. A cathedral should have seven bells in its tower, but a minimum of five is allowable. Even the humblest church should have a bell that can be played in two distinct manners.14 Although the tower is to be of solid construction, the actual belfry should be open on all sides to allow the sound of the bell to radiate in all directions.

Towers should have a fixed cross at their apex. A clock and a weather vane may be incorporated into a bell tower's design. The clock's face should show the day's third, sixth, ninth, and twelfth hours to mark the times of the Divine Office. The vane should have two components. The tower's fixed cross may serve as the vane's fixed shaft. The vane's variable component should be the figure of a cock. The fixed cross represents the solidity of faith, while the moveable vane's cock form represents both perpetual vigilance and the variability of all things other than faith.15

A church's interior organization, furnishings, and decoration are the focus of a major portion of Borromeo's Instructiones. Borromeo identifies that a church's main altar and sanctuary should be the nave's axial focus and each transept arm can accommodate a side altar. If a church does not have a transept and/or if the side aisles are of sufficient width, side altars should be the axial focus of a church's side aisles.16 In discussing a church sanctuary's design, Borromeo states that a sanctuary's floor level should be an odd number of steps above that of the nave and side aisles. If circumstances permit, the sanctuary's floor finish should be of a more durable, refined, and carefully crafted material than that of the nave and aisles. The sanctuary's vault should contain mosaic or other decorative work. A railing at which the congregation receives communion should separate the nave from the sanctuary. The sanctuary's size should be adequate to accommodate those solemn occasions that involve a large number of clergy.

The main altar holding the Blessed Sacrament tabernacle should be the principle object of focus in the sanctuary while also accommodating the saying of Mass. It should rest at least one step, if not three steps above the height of the sanctuary's floor level. Side altars should support devotional statues and contain reliquaries. Side altars may directly adjoin a wall but the main altar must be freestanding. The main altar should be made of solid stone or faced with marble and must contain relics of at least two saints. If the main altar is not made of solid stone, an altar stone containing relics, which is also identified as a portable altar, should be within the altar's top surface.

Borromeo conveys that a decree issued by his regional provincial council of bishops stipulated that the Blessed Sacrament tabernacle should rest on the main altar.17 This requirement became a part of the Church's rubrics in 1614. The Ceremonial for Bishops, which was in effect in Borromeo's episcopal province when he wrote the Instructiones, stipulated that in contrast to the requirement for parish churches, the Blessed Sacrament tabernacle in a cathedral was not to be located on its main altar. A cathedral's tabernacle was to rest on an altar within a separate chapel that was dedicated to that purpose and which was adjacent to the sanctuary. Voelker observes that the Apostolic Constitutions, a fourth-century treatise on religious discipline that was a part of the tradition Borromeo drew upon, identified that within the sanctuary of a cathedral:

. . . in the middle, let the bishop's throne be placed, and on each side of him let the presbyters sit down.18

Such an arrangement required that the altar be located between the body of the nave and the bishop's cathedra. Borromeo states that the prohibition against placing the tabernacle on the altar in cathedral churches was motivated by the desire to maintain an unimpeded visual sightline between the cathedra and the congregation. Borromeo's resolution of this requirement within his archdiocese was to raise the tabernacle on columns above the altar, maintaining a line of vision between the congregation and the cathedra. In circumstances where the cathedra, the altar and the tabernacle are all in axial alignment with the nave, a freestanding or suspended canopy, a baldachin, should be placed over the altar and tabernacle.

Borromeo envisioned that most church services would occur during daylight hours when a church's interior would receive natural light. Despite this circumstance, Borromeo stipulates that certain candles or oil lamps must burn inside a church's sanctuary, regardless of the natural illumination levels within the building.19 This requirement was prompted by Catholics' identification of a burning flame as a symbol of Christ's presence, because of Christ's self-identification as "the Light of the World."20

The required artificial light sources within a church's sanctuary include a lampadarium, which is a lantern whose flame is referred to as the sanctuary light.21 The lampadarium contains either oil lamps or candles and should be located in visual proximity to the Blessed Sacrament tabernacle. The sanctuary light is to burn whenever the Blessed Sacrament is in the tabernacle. The lampadarium should have three or five lamps; seven in large churches; or a minimum of one in smaller churches. In addition to having the lampadarium close to the tabernacle, six candlesticks should be on the main altar.22 Only two of the altar candles are to burn during most liturgies, but four or six should burn during Solemn or High Mass and other special observances. In addition to the six candlesticks, Borromeo identifies that a crucifix should be on or above the main altar.23 Should a church have a diaphragm arch above its sanctuary, the crucifix should be on the diaphragm wall above the arch.

Borromeo does not establish definitive placement for a church's ambo, which accommodates the proclamation of scripture, or for a pulpit, which accommodates preaching. He states that these furnishings should be convenient to the altar, not block the congregation's view of the altar, and be situated so the congregation can easily see and hear the ambo's or pulpit's occupants. Borromeo states that ideally there should be two ambones, one accommodating the reading of the Gospel, the other the epistle. From the congregation's viewpoint, the Gospel ambo should be on the nave's left side and the epistle on its right. A single ambo can fulfill both functions if circumstances dictate that there only be a single ambo. In those circumstances it should be on the Gospel side.

Sacristies should be adjacent to the sanctuary. Ideally, a church should have two sacristies. One would be next to the main sanctuary and the other would be located close to the church's entry doorway and provide storage for vestments and a place where the ministers could vest. The vesting sacristy's location by the church's entry doorway allowed the priest who was saying Mass to initiate and close liturgies with a formal procession, an ancient Church tradition. At the bishop's discretion, more modest churches could function with only one sacristy if it was located close to the sanctuary.

Four chapters of Borromeo's Instructiones present directives regarding additional furnishings for a church. Two chapters deal with sacrariums i.e., special sinks for washing altar linens and other items associated with the Mass; and furnishings to enforce the segregation of the congregation by gender. A lengthy chapter contains a discussion of baptisteries. Detailed specifications are provided for baptisteries that could accommodate baptism by immersion or affusion, placing either the required pool or pedestal type baptistery within a stepped depression so as to signify descent into a sepulcher. A cathedral's baptistery should be freestanding, while those of most churches ideally would be located within either a chapel or in front of an altar at the rear of the church on the Gospel side, although it could be located on the epistle side. The directives regarding confessionals focus on providing privacy for the penitent while simultaneously removing any appearance or avenue for inappropriate conduct or pecuniary gain on the part of the confessor. Detailed dimension and material requirements are recommended for baptisteries and confessionals.

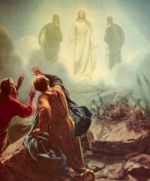

Two chapters and portions of others in the Instructiones identify directives regarding the use of decoration, religious images, relics, and graphic inscriptions within churches. In 1563, the Twenty-Fifth Session of the Council of Trent had issued a statement "On the Invocation, Veneration, and Relics of Saints, and on Sacred Images."24 Within this statement the Council reiterated the Second Council of Nicaea's position regarding these issues, i.e., that Christian dogma makes images, especially images of Christ, imperative, as in them, "the incarnation of the Word of God is shown forth as real and not merely phantastic." Nicaea II extended this justification of religious imagery beyond pictorial representations of Christ, by stating:

with all certitude and accuracy that just as the figure of the precious and life giving Cross, so also the venerable and holy images, as well as in painting and mosaics as of other fit materials, should be set forth in the holy churches of God, . . . the figure of Our Lord God and Savior Jesus Christ, of our spotless Lady, the Mother of God, of the Honorable Angels, of all the saints and of all pious people.25

Borromeo's directives regarding iconography and art admonish bishops that it is their responsibility to ensure that the subject matter and quality of the images in churches and the honor shown the images be appropriate. Within his episcopal province, Borromeo required bishops to instruct pastors and artists of their responsibilities in this regard, and to enforce fines or punishment against pastors and artists who failed to fulfill those responsibilities. Borromeo specifically stipulates that window glazing should incorporate images of the saints. He also states that sacred images should not be incorporated into pavement patterns, where the potential would exist that the images would not receive proper veneration. Borromeo recommends that saints' names should be written under their images if the image's identity is at all obscure. He also admonishes that great care should be taken that the images within a church represent historical truth or valid theological teachings.

Two Church publications were mainly responsible for disseminating Borromeo's directives beyond the bounds of the Archdiocese of Milan. These were the description of "The Church and Its Furnishings" in the Roman Missal, and the "Instructions for Consecrating a Church" in The Ceremonial of Bishops.26 Borromeo was the principle author of both of the revised versions of these documents which resulted from the Council of Trent's deliberations. Although these publications were modified several times over the centuries, the portions regarding church design remained relatively unchanged and generally were adhered to with minor exceptions worldwide until the twentieth century.27

Catholicism is an inherently conservative tradition and one that historically has recognized tradition's authority. The United States' National Conference of Catholic Bishops' Committee on the Liturgy's Environment and Art in Catholic Worship (1978) was the first document pertaining to Catholic churches in the United States that sought to revise the guidelines contained in the Instructiones. that document recently has been superseded by Built of Living Stones: Art, Architecture, and Worship (2000). While these documents attempt to address the impact of the Second Vatican Council's reformed liturgy on the design and furnishing of Catholic churches, those parts of Borromeo's Instructiones that are rooted in Catholic theology should not be ignored.

Notes

1. Committee on the Liturgy, Environment and Art in Catholic Worship (Washington DC: National Conference of Bishops/United States Catholic Conference, 1978); idem, Built of Living Stones: Art, Architecture, and Worship (Washington DC: National Conference of Bishops/United States Catholic Conference, 2000).

2. In this article Evelyn Carole Voelker's, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones Fabricae Et Supellectilis Ecclesiasticae, 1577: A Translation With Commentary and Analysis, (Ph.D. Diss., Syracuse University, 1977) is quoted. Voelker's dissertation has three distinct portions; a translation of Borromeo's text, notes on the text, and commentary. To distinguish here between Borromeo's text and Voelker's notes and analysis, whenever reference is made directly to Borromeo's text, the citation appears as: Borromeo, Instructiones, and the page number. References made to Voelker's notes and analysis are cited as: Voelker, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones, and the page number. In both instances, the pagination refers to Voelker's text.

3. Borromeo, Instructiones, 21-23.

4. Michael Andrew Chapman, The Liturgical Directions of Saint Charles Borromeo, Liturgical Arts 3-4 (1934): 142; Richard McBrien, Lives of the Popes, (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1997), 287-289; R. Mols, Charles Borromeo, in New Catholic Encyclopedia; Voelker, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones, 53.

5. Quotations from Durandus in this text are from: William Durandus, The Symbolism of Churches and Church Ornaments, trans. John Mason Neale and Benjamin Webb (Leeds: T. W. Green, 1843).

6. Voelker, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones, 43-44.

7. Borromeo, Instructiones, on siting see: 35-38 and 122, 359; on the sanctuary's alignment see: 124.

8. Palladio quotation in Voelker, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones, 45.

9. Robert Jan Van Pelt and Carroll William Westfall, Architectural Principles in the Age of Historicism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 138-167.

10. Borromeo, Instructiones, on church plan configurations see: 51-52; on a church's interior alignment see: 124, 125; on church entrances see: 75 and 287; on floor area requirements see: 38; on church facades see: 63-64; on the number of doors see: 97-99; on windows see: 109-112.

11. Alberti quotation in Voelker, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones, 117-118.

12. Durandus, The Symbolism of Churches and Church Ornaments, 29.

13. Borromeo, Instructiones, 326-330.

14. This is generally accomplished with a mallet that strikes the bell when it is not tolling, and by tolling the bell, which causes the suspended gong that hangs within the bell to strike the moving bell. The ritual ringing of the Angelus and other occasions that elicit bell ringing require these two types of bell tones; see Durandus, "Of Bells," in The Symbolism of Churches, 87-97.

15. Durandus, cited in Voelker, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones, 336.

16. Borromeo, Instructiones, for the sanctuary's size and the construction and location of altars, see: 143-148 and 194-197.

17. Borromeo, Instructiones, 160; and Voelker, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones, 164-168. Voelker establishes that prior to the Council of Trent, the tabernacle was sometimes within a niche on the Gospel side of the sanctuary, in a pyx in the shape of a dove hanging next to the altar, or within a tower somewhere in the sanctuary. Prior to the legislation of 1614, bishops or provincial synods had the discretion to determine the tabernacle's location within cathedrals.

18. Voelker, Charles Borromeo's Instructiones, 138.

19. Borromeo, Instructiones, 243-245.

20. John 8:12, The New American Bible; Durandus, The Symbolism of Churches and Church Ornaments, 29.

21. Borromeo, Instructiones, 243-245.

22. Michael Andrew Chapman, The Liturgical Directions of Saint Charles Borromeo, Liturgical Arts 4 (1935) 109.

23. Borromeo, Instructiones.

24. Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent, English trans. by J. J. Schroeder (Rockford, IL: Tan Books, 1978), 215-217. Quotations regarding Nicaea II from: "The Council of Nicaea II, 787," in Leo Donald Davis, The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787): Their History and Theology (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1983, 1990 ed.), 309, 310.

25. Information regarding these publications taken from The Roman Missal in Latin and English, (New York: P. J. Kenedy and Sons, 1930), xxvi-xxvii.

26. There were two directives that were commonly ignored even during Borromeo's lifetime. One prohibited providing views from private residences into churches for use by wealthy individuals. Examples of the disregard of this directive include Rome's Pamphili Palace and Church of San Agnese (1645-1650, 1653-1657), the Royal Chapel at Versailles, and the Residenz in Wurzburg, Germany. The other directive that generally was ignored required that men and women be segregated not only within churches, but while receiving the sacraments or even upon entering or leaving a church.

Matthew E. Gallegos, Ph.D. is professor of Architectural History in the College of Architecture at Texas Tech University and a registered architect.

© The Institute for Sacred Architecture

This item 6445 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org