What Chesterton wrote to his wife when she entered the Church

By Dr. Jeff Mirus ( bio - articles - email ) | Dec 18, 2025

In 1901, Gilbert Keith Chesterton married Frances Alice Blogg. As the Catholic world knows now, Chesterton was a prolific thinker and writer who operated through genius more than well-organized habits, and Frances (who was also a writer) often served as his secretary and kept him on track. By all accounts, including their own, they were deeply in love, and it was a sadness that they were unable to have children. But some of Chesterton’s literary energy was directed toward his wife, to whom he wrote many poems.

When he and Frances married in 1901, neither of them was Catholic. Chesterton became convinced of the veracity of Catholicism and converted about twenty years later in 1922. Frances, born in 1869 and almost five years older than her husband, entered the Church four years after he did. Apparently one of her greatest points of hesitation was the Catholic teaching that Christ was not just symbolically present in the Eucharist but really, truly and completely present “body, blood, soul and divinity”.

Having been slow to enter the Church himself, Chesterton was understanding and patient. But when Frances was received into the Church, he marked the occasion by writing another poem to her with the title “The Two Kinds”. I presume that this title calls to mind, at one and the same time, the two kinds of Eucharistic Presence (under the appearance of bread and wine), the two kinds of human person (created male and female), and perhaps even the two kinds of responses to Christ (believer and non-believer). Here is the poem:

THE TWO KINDS

To others of old I would have said

That dogmas deep as questioning Christendom

Sleep in the sundering of the wine and bread,

And that Incarnate Christ in every crumb.

For you I find words fewer and more human:

Content to say of him that guards the Shrine

“To drink this Wine he has lost the Love of Woman

Yea, even such love as yours: to drink this Wine.”

The identity of “him that guards the Shrine” is not clear, at least to me. It could, I suppose, be any of the following (or all at once): Chesterton, each and every believer, each and every priest, and Christ Himself. Perhaps deeper readers will discern the sure fullness of the phrase, but I find this poem more powerful precisely because of its ambiguity, and so I will offer some possible interpretations.

First, it is possible that Chesterton is saying that even he would be willing to lose his wife’s love to “drink this Wine”. There seems to have been no question of that being an issue, but it was undoubtedly painful for Chesterton to take the risk of entering the Church when his wife had as yet no inclination (or at least no commitment) to do so. I do not think this is the primary meaning of the line in question, but one of the most powerful aspects of good poetry is the ability to capture multiple levels or layers of reality at the same time. So there may be an echo here of just such a concern, and certainly Chesterton regarded himself in some sense as a guard of that Shrine which is the Church.

Second, of course, “him that guards the Shrine” could be a reference to any Catholic who is forced in any degree or at any level to place Christ first without the understanding of those he loves, especially a spouse or potential spouse. This issue frequently arises in Catholic courtship, and can certainly become a serious difficulty in later conversions to Catholicism. Marital friction over Chesterton’s own conversion was unlikely—and yet so great a difference between spouses who care about the truth is never easy, never to be taken lightly or ignored.

Third, the guardian of the shrine referenced in this poem might well be any priest or all priests who, at least in the Roman Rite, are celibate and must, as a very direct price of their guardianship, forego a woman’s love. In this sense, Chesterton again pays his wife a very great compliment, in that the priestly guardian must be willing lose “even such love as yours, to drink this Wine”. However interpreted, this phrasing declares how highly Chesterton values both the Eucharist and his wife’s love.

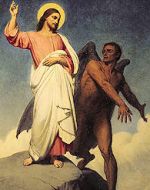

Finally, there may be a sense in which Christ Himself is the guardian of the Shrine—that is, the guardian of His own body “given for you” within which courses his own blood “poured out for you” (Lk 22:19-20). Much has been made over the centuries (and in some modern movies) of Christ’s sacrifice of the marital embrace, a possibility He definitively eliminated in the more complete sacrifice of His own life on the Cross as soon as he had reached the full maturity of his manhood. Just as for priests who renounce marriage for the sake of the Kingdom, this is at at least one part of Our Lord’s absolute renunciation in his agony in the Garden of Gethsemane.

And here we have also the imagery of the cup, indeed the very wine of self-sacrifice, as Our Lord prayed: “Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me. Yet not as I will, but as you will” (Mt 26:39). This certainly signifies the ultimate guardianship of that shrine from which would pour forth the very salvation of the world. But what or whom is Christ really guarding? How generously does He guard? And how blessed are all who accept His protection—to eat…and drink…and live!

All comments are moderated. To lighten our editing burden, only current donors are allowed to Sound Off. If you are a current donor, log in to see the comment form; otherwise please support our work, and Sound Off!