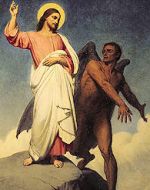

Religious art and life: Recognizing the beauty of goodness

By Dr. Jeff Mirus ( bio - articles - email ) | Jan 12, 2026

A fine recent article on the late Renaissance painter Caravaggio* reminded me that artistic brilliance may not always be matched by moral achievement. This is a problem that plagues everyone in every walk in life, but it is particularly annoying when the moral reputation of an artist stands between his work and our ability to appreciate it. It is even more annoying when our own preconceptions prevent us from appreciating the goodness before us.

The current furor over the art of Fr. Marko Rupnik is a contemporary case in point, especially since this relationship between the morals of an artist and his work is particularly difficult to ignore in religious art. It is, of course, more difficult to ignore in art used to adorn churches, still more problematic while the artist is still alive, and particularly striking when the artist is a priest or religious.

But the passage of time does make some difference. After a century or two it becomes easier to separate in one’s mind the beauty of a work of art from the moral ugliness of its creator. It also becomes easier to admit that artists, like all the rest of us, are complex beings, sometimes even notorious sinners who have, nonetheless, been in their own way touched by grace.

Artistic peril

I do not have a solution to this problem. It really is spiritually destructive when the notoriety of an artist causes us, in the midst of attempting to find spiritual nourishment, to be reminded of the repulsiveness of the maker instead of the beauty of what has been made. This is one of the great problems we face in the selection and use of all sacred art. Whenever it is publicly associated with serious moral scandal, it must largely fail in its purpose, calling to mind not the victory of grace but the perennial power of sin.

At the same time, great artists have a special ability to highlight deep aspects of reality which we would otherwise miss. It might be best for sinners not to attempt to immortalize the good but then nobody but Our Lord and Our Lady could do it. Analogously, only an abject coward would decide not to conceive a child because that child might suffer from the moral deficiencies of the world into which he or she must inescapably be born. Attempting to create any form of spiritual beauty is artistically akin to conceiving a child and doing one’s best to form that child to be another agent of good, another servant of the very goodness that is God Himself.

The work of the painter or the sculptor or the architect can participate in the goodness of God, in a manner similar in some ways to what a parent achieves by raising a child well. By an admittedly loose analogy, we also see that as the child can be perverted by the imposition of false goals and desires, the work of art can be marred in its creation by both the material and spiritual deficiencies of the artist.

A work of inanimate art, of course, cannot misinterpret or abuse itself as a human person can, nor can it overcome the deficiencies of its creator through its own acquisition of grace. But the beholder can bring his own store of grace to the perception of a work of art, perhaps in ways similar to the person who recognizes the good in another person and discloses that good not only to the one seen and appreciated but to others who may be able to learn to see, and so to appreciate, in new ways.

Seeing and being seen

It is said that art imitates life, but it is never said that art actually is life, and this means the artist must always be selective. He or she cannot capture the whole of life but must highlight selected aspects in order to convey something that is inescapably partial with a certain freshness and power. This means, of course, that art does not fully imitate; such power is quite beyond its scope! But it does call attention to those aspects of the larger reality that the artist has in view, aspects which are communicated with a particular freshness and so effect a deeper penetration in the one who looks, and contemplates, and at length awakens to the artistic vision.

We too are works of the most exquisite art. To the casual observer we may seem flat, dull, repulsive or simply lacking in richness. But that is not the case for the Divine artist, and neither is it the case for those who strive through a kind of serious humility to see what the Divine artist sees—what, in truth, the Divine artist has wrought.

O Lord, you have searched me and known me! You know when I sit down and when I rise up; you discern my thoughts from afar…. For you have formed my inward parts, you knitted me together in my mothers womb…. Search me, O God, and know my heart! Try me and know my thoughts! And see if there be any wicked way in me, and lead me in the way everlasting. [Ps 139 [138]: 1-2; 13; 23-24]

Good artists see something in reality that they wish to highlight and capture to signify their own reception of what is good and beautiful, and to communicate that to others. But what about us? Do we see what is good and beautiful in a particular person and seek to draw that out so it becomes more visible to others, and even to the person himself?

The mystery of any art is bound up with both the mystery of the artist and the mystery of what the artist sees. Sadly, in art and especially in the art of life there is much that we simply do not see, much indeed that we fail to look for at all. But as we learn to see as God sees, we discern truth, goodness and beauty, in both ourselves and others.

This is what God’s love does within us. It enables us to discern the good, to affirm its presence, to cultivate it and enable it to blossom. The Divine artist in each of us can recognize what is good, can highlight it and draw it forth, can affirm it as especially worthy of God’s love. Our artistic mission, as sons and daughters of God Himself, is to recognize this remarkable goodness and to call attention to its unique qualities. Our goal is for each person to recognize in himself the Divine image, and for others, transcending their perceptual limitations, to see the tremendous beauty of each child God has made.

* “Caravaggio and Us” by Jaspreet Singh Boparai in the January 2026 issue of First Things. Depending on your usage patterns, you may or may not be able to read it online without a subscription.

All comments are moderated. To lighten our editing burden, only current donors are allowed to Sound Off. If you are a current donor, log in to see the comment form; otherwise please support our work, and Sound Off!

-

Posted by: jsg9932 -

Jan. 19, 2026 11:10 PM ET USA

There is one case when art actually is life. It's when God is the artist. God speaks and the world is created. The human artist expresses truth when their art matches reality. God expresses truth when reality matches His Word. It's interesting that the impact of evil and immorality is reversed, too. The immoral artist turns people against the art, whereas evil in the world turns people against God.

-

Posted by: espacia24421 -

Jan. 16, 2026 10:09 AM ET USA

It didn't take the passage of time for me to see Rupnik's hack work for what it is: hack work. I disliked it long before his crimes against women and God became news. It panders to the zeitgeist and distorts what is beautiful in Christian iconography.