Living the Will of God: Vocation, Avocation, and Moment to Moment

By Dr. Jeff Mirus ( bio - articles - email ) | Jul 05, 2012

As many of my long-time readers know, I enjoy sailing small boats. As a result, I’ve also read a good deal of literature by and about sailors. Much of this comes from full-time live-aboard sailors or those who have circumnavigated the world in smallish craft. It’s a life that brings one close to nature, with plenty of time for reflection, and that reflection almost invariably produces a sense of one’s own smallness. As a result, such writing is generally insightful, often exciting and sometimes even poetic. But authors in this genre tend also to make unflattering comparisons between sailors and the rest of mankind. And that’s where I draw an important line.

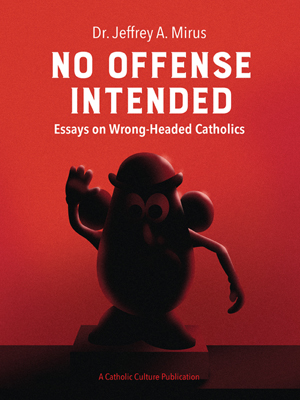

Free eBook:

|

| Free eBook: No Offense Intended |

Everybody has a secret dream, so the argument goes, but few have the courage to live their dream. The sailor casts off his moorings and goes, and this (he too often claims) makes him a superior sort of person—a person who overcomes the petty restrictions of landlubber life, restrictions such as work, the monthly anxiety of meeting the mortgage payment, useless conventions and constant schedules. In book after book, sometimes sympathetic and sometimes not, sailing authors parrot that venerable American fraud, Henry David Thoreau, expressing the conviction that (unlike himself, of course) “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” Or, in the even more famous words of Dr. Seuss in his alphabet book, On Beyond Zebra: “Most people stop with the Z…but not me!”

Now it is a sad thing when any person, after reasonably concluding that some personal aspiration is consonant with his larger and higher responsibilities, fails to attempt to fulfill that aspiration out of a sort of debilitating timidity or, as is perhaps even more often the case, out of laziness. It is even sadder when we allow ourselves to be bogged down (as, yes, all of us do at times) in secondary, inessential and ultimately inconsequential or even damaging preoccupations, so that we lose sight of more important goals and even potential achievements. Put this way, the situation is almost a paradigm for what might be wrong with our spiritual lives.

But the sailor’s conclusion (or any similar conclusion) does not follow. It is simply not the case that those who throw off all constraints in order to follow their desires are superior to those who are unwilling to do so. For the truly superior person resolves not to do his own will but the will of God. He constantly tests his own desires against God’s will, doing his best to discern the difference between purely natural inclinations and those interior movements of the Holy Spirit which indicate some solid and enduring aspect of God’s plan for his life.

Vocation

Given this introduction, no reader will be surprised that another frequent theme in articles written by sailors is marital breakup. I have encountered many self-revelatory comments about how a sailor’s love for his boat gradually separated him from his wife and his children until divorce became inevitable. The remarkable thing is a tendency to place the blame on the non-sailing party who, without doubt, really was by that point leading a life of quiet desperation. But this raises the key question. How do we discern God’s will? When we are talking about setting out on a life-long course of following God’s will, the answer begins with our response to a general vocation, a call by God to a particular state in life.

This notion of vocation is supremely liberating. Nobody can go through life attempting to learn and follow God’s will with respect to every aspect of life at every moment. This just isn’t possible. And if it is not possible, it means God does not ask us to do it. Instead, He ordinarily places us in a context in which the broad outlines of His will are clear. We all start out as children, for example, and while we are children, this state in life dictates and conditions nearly all of our responsibilities. Even as children, if we work at these responsibilities, doing the will of God can become habitual. In this as in any other “state-in-life” vocation, there can be upheavals. A parent may die, or have severe problems of one sort or another, and this may prompt new questions and responsibilities, especially if we are at an age at which our “purely” child status is nearing its end. But such upheavals are not continuous.

The same is true as we mature and prepare to strike out “on our own”. We will not really be on our own, of course, for now the well-formed person—the person who knows that both accomplishment and happiness consist in doing God’s will—seeks to know what new state of life God calls him to. It may be the priesthood, religious life, or some other form of consecrated single life; or it may be marriage and family; or it may be the single state with no formal consecration, which frees the person for kinds of service which are not as specifically pre-patterned as in the other states, or kinds of service that those in other states could never undertake. (I part company here with those who argue that there is no such thing as a vocation to a single life that is not formally consecrated. But all of us are in the single state while discerning our vocations, and by its nature a vocation to the single state is more easily open to change.)

One discerns a vocation, as one discerns every not-yet-known aspect of God’s will, in prayer. But once a person understands his or her fundamental call and follows it, fidelity to this state-in-life vocation really is tremendously liberating. Far from imposing petty restrictions which prevent a person from realizing his deepest aspirations, the vocation provides a framework within which a person can more easily realize his deepest aspiration to follow God’s will more fully. This is precisely because a great many of the foundational decisions are now settled.

A priest knows that God’s will for him is framed by obedience to an ecclesiastical superior and a life of sacramental ministry. A married person knows that his family provides the pattern for what it means to make all of his decisions in accordance with the will of God. Those in consecrated life inherit a spiritual regimen and a structure of spiritual authority. Even the person who is by vocation single will seek to serve others in a manner, or to a degree, not possible for those whose vocations by their very nature impose specific limitations on their ordinary activity.

Avocation

The single person will be left with more to discern, of course, and in any case no state-in-life vocation is necessarily permanent. A spouse may die, thrusting a married man or woman back into the single state; a person called to the single state for an extended period may, in time, find himself called to marriage or priesthood or religious life; religious orders sometimes fail or are suppressed; even priests, with or without personal fault, may be occasionally laicized. So conditions may arise in which any given person may have to discern again what his fundamental vocation is, that vocation which provides the basic framework for his overall pattern of life.

More commonly, however, within a well-understood vocation, each person must also discern what is often called an avocation. Unfortunately, this word can sometimes be used to refer to one’s principal vocation, and at other times to a hobby. But I use it here to indicate, within a state-in-life vocation, the particular occupation a person will pursue. This too can change, usually more frequently than a vocation, but such moments of avocational decision are still relatively rare. In any case, like the vocation, the avocation or occupation must be discerned in prayer.

Generally a vocational decision will heavily color an avocational decision, and sometimes a very broad avocational decision will color a more specific one. For example, in some cases a person who is a priest or religious will be assigned particular work, but there will often be an opportunity for both the person in question and the superior to discern what particular work God is calling the person to do. In a similar way, a person who joins the military may have greater or lesser control over the specific job to which he or she is assigned. Moreover, the daily work or even career of a husband or a wife will be (or should be, whenever possible) circumscribed by the demands of family life. A consecrated single person may make avocational decisions in part with a specific community in mind. An unconsecrated single person may have a wider scope for decision, but will rarely be free of external constraints (geographical location, ability, the needs of relatives or friends).

In fact, it is precisely through the full variety of possible constraints (including, of course, our own particular gifts) that God most commonly indicates to us the avocations He wishes us to pursue. Very frequently, several possibilities will come to mind in prayer and reflection, either all at once or over time. But quite often only one actual opportunity will present itself in a compelling way, or even in any way at all. God’s will is perhaps more commonly—and more easily—read in the light of real opportunities than in any other way.

But even the real possibilities must be discerned in prayer. God is capable of communicating possibilities to us which we would otherwise miss. In addition, there still remains the sailor’s dilemma: When is our desire to follow a certain path a temptation, and when does the temptation lie in our reluctance? When is our conviction that we are incapable of doing something an intuition from the Holy Spirit, and when is it the Holy Spirit’s challenge to overcome our fear? Frequent prayer (including frequent and reverent reception of the sacraments), accompanied by spiritual direction whenever that will be helpful, is the only way to properly discern God’s will. And even when receiving spiritual direction, it is never the director’s place to make the decision, but only to help us learn better how to discern God’s will.

The Sacrament of the Present Moment

Where are we now in our consideration? We have discerned what I call our state-in-life vocation, and within that we have discerned our avocation, that is, our ordinary occupation. Both of these decisions impose general and specific frameworks within which, as long as we are in this vocation and avocation, tell us a great deal about what we must do to fulfill the will of God in our daily lives. They will provide a system of devotion (or at least imply the general means by which we ought to develop our spiritual life). They will give us both an overarching mission and a fairly comprehensive set of specific responsibilities. They will very largely govern the use of our time. Within the topic of this essay, “Living the Will of God”, they will invariably make our decisions far easier than they would otherwise be. Finally, they enable us to develop specific habits which ensure that we are busy with God’s will much of the time.

But we must also realize that the vocation and the avocation do not complete the process of living the will of God. For as long as we are in this vocation, and for as long as we are in this avocation, many of our decisions are fixed. But within the vocation and the avocation there are a million possible variations. Moreover, as a general rule, no vocation or avocation occupies all of our time with its specific set of concrete responsibilities. This means that even within these liberating frameworks, we must continue the process of discerning God’s will. Rooted firmly and serenely in our vocation and avocation, we must seek his will moment by moment. Or as Fr. de Caussade so admirably puts it in his masterwork of spiritual direction, Abandonment to Divine Providence, we must seek to live always in the sacrament of the present moment.

Consider: Periodically I may have the opportunity to choose a new project or a new emphasis in my occupation; always I have this opportunity in my spare time. In addition, my direct superior may change, or my workload or habitual method of operation may be altered or even disrupted. Moreover, at any moment of the day there may arise a new possibility for me to consider. Or, very likely, I will frequently experience interruptions, which may be welcome or dreaded, but which (I may be sure) are Providential. How will I respond to each new possibility, each fresh interruption? What does Our Lord have to say about it? In which direction am I inclined by the Spirit of God?

Here the sailing analogy is fairly useful. The one thing sailors must learn to do is depend on wind and weather. This is why sailors tend to develop patience and a philosophical outlook on life, in the sense of discerning the difference between what they can and cannot control, and recognizing their inescapable dependence on many surrounding circumstances. Their progress, and sometimes their lives, will depend on making the right adjustments to these circumstances. And this is precisely what each of us is called to do, first and foremost in our spiritual depths, and then in every thought, word and action which flows from who we are and who we wish to become in Christ.

To refer to Fr. de Caussade’s advice again, the chief obstacle to discerning and doing God’s will—whether for our vocation, avocation, or moment to moment—will always be self-love. We are annoyed by something because of our complacency; we are offended by someone because of our pride; we put off doing this or that because it is outside our comfort zone; we rush hither and thither because we find it diverting or entertaining; we avoid some people because they strain our charity, and we avoid some causes because they strain our pocketbooks; and of course we curry favor here and there, wherever it pampers our conceit. “Self love!” cries Fr. de Caussade, and he is right.

Self-love is in all cases the preeminent obstacle to spiritual advancement, and therefore to doing God’s will. If only Thoreau and my sailing exemplars knew what causes us to lead lives of quiet desperation! They would soon learn that they cannot long escape such a fate by changing their location on the face of the waters. They would learn the difference between fruitful recreation and flight from responsibility. They would, in other words, realize that both success and happiness in life come from seeking and doing God’s will. Remarkably, some do find this message blowing in the wind, even though they habitually separate themselves from the sacraments by living on a boat. But for most of us, the heavy spiritual lifting necessary to reach life’s true goals is done where we find ourselves, close to home—more firmly grounded than all those who are essentially at sea.

All comments are moderated. To lighten our editing burden, only current donors are allowed to Sound Off. If you are a current donor, log in to see the comment form; otherwise please support our work, and Sound Off!

-

Posted by: dschenkjr9859 -

Jul. 06, 2012 10:48 PM ET USA

This is all too complicated for me. Reminds me of someone analyzing a golf swing with all of its facets and nuances. I feel God gives each of us an envelope or a playing field. What happens on that field is pretty much up to us. We can pray to God for help and he will provide it. But by and large, He lets us play the game and hopefully play it according to His rules as per the Bible and as per the Catholic Church. Vocation..avocation... God's will – maybe so but only in the broadest of terms.