In York with a martyr: The challenge of Margaret Clitherow

By Dr. Jeff Mirus ( bio - articles - email ) | Jul 02, 2019

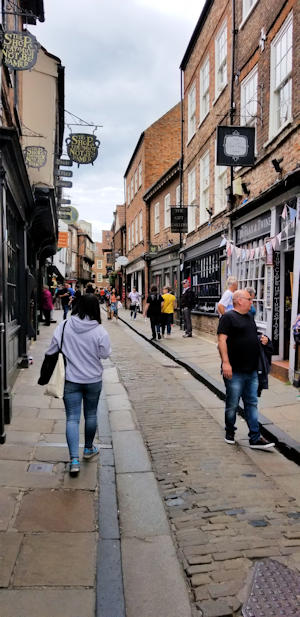

The Shambles, a narrow street housing butchers where the Clitherow family lived

The exterior designation of the shrine in (or at least very near) St. Margaret’s home

The interior of the shrine, with statue of St. Margaret on the left

The plaque on Ouse Bridge which commemorates St. Margaret Clitherow’s martyrdom at the no longer existing Toll Booth

It is impossible to visit England without reflecting on how much the Church has suffered here. One tours successive Gothic cathedrals which now offer only anemic Anglican “services”. Today I am writing from York, having foregone the visit to the famous York Minster, one of the largest Gothic cathedrals in Europe. I am thinking instead about Margaret Clitherow, who is commemorated by an exceedingly modest shrine near her home in York and by a small plaque, set in 2008 on the Ouse Bridge, which marks the place of her martyrdom in the Toll Booth some 422 years earlier.

But to be fair, that’s just me, and if I hadn’t felt the need of a break, I might well have visited the Minster, even if St. William of York (d. 1154) is still turning in his grave. It was built, after all, like everything that best reflects ultimate reality, by the sons and daughters of the Church founded by Jesus Christ. With Saint Margaret, though, we might prefer the crucifix to Gothic splendor, as the best possible case in point.

Margaret’s life and death present a study in another historical phenomenon, the rapid ease with which human cultures slide between truth and falsehood based on the whims of those who are accounted great. We see exactly the same thing in the rapid downward cultural spiral of our own time. But what is most remarkable about Margaret is that she actually became a Catholic during the days of the Elizabethan persecution. One is reminded of the observation that only a dead dog drifts with the current. Margaret was very much alive—and so to preserve decorum, of course she had to be martyred.

Following the execution, Queen Elizabeth is said to have written to the citizens of York to lament that the death penalty had been meted out to a woman—proving, one supposes, that the Queen was innocent of at least the sin of feminism.

Death under pressure

Margaret Middleton married a wealthy York butcher and Chamberlain of the City, John Clitherow, in 1571 at the age of 15. Ten years later, knowing her own mind, she converted to Catholicism. Her husband, though a member of the established church (Anglican), was not unsympathetic; his own brother was a Catholic priest. So John willingly paid the fines for Margaret’s non-attendance at Anglican services. Nonetheless, she was imprisoned three times for her failure to attend, beginning in 1577, with the final imprisonment extending nearly two years. Margaret was very tough: She bore her third child in prison.

But Margaret did far more than refuse to participate in heretical rites. She also sent her eldest son to the English College in Rheims to study for the priesthood, which in itself led her husband to be closely questioned by the authorities about why his child had been sent abroad. She hid Catholic priests, purchasing a second house in the famous butcher’s district (the Shambles) for this purpose, since her own home was so closely watched. And of course she arranged for Mass to be said in that house for the local Catholics. Unfortunately, during a search of the premises, a terrified youngster was induced to reveal the priest’s secret hiding place—the “priest’s hole”.

Given Margaret’s extraordinary constancy, this discovery sealed her fate. The mother of four, Margaret refused a trial by jury so that her older children would not have to be questioned. Therefore she was executed by the standard method used to extort a confession. With her youngest child still in the womb, Margaret was laid upon the ground, with a rock the size of a large apple beneath her backbone. Then her own door was placed over her and gradually weighted with roughly eight hundred pounds of stone, until her back was broken and she died.

Or, I should say, until they died.

And what about us?

According to a website devoted to the history of York, Margaret’s stepfather, Henry May, the Lord Mayor of York (her father having died when she was 14) “accused her of committing suicide, and others decried her as being mad.” But in the sense in which the Lord Mayor used the term “suicide”, every martyr may be dismissed as having merely taken his own life by reason of insanity.

We, on the other hand, maintain that the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church, and so we not only should but must believe. Even so, the connection between such death, germination, and growth is seldom clear, and may not be witnessed for generations, or may never be witnessed in the same geographical region at all (for all we know so far). I have said before that there is a larger Providential character to history which we cannot read completely, and so it is difficult to fully explain why the Faith thrives in human culture in one place for a season, and then slowly diminishes or is more abruptly cut off, while taking root in another culture, or perhaps in some places never germinating at all.

It is extraordinarily hard for us to discern that good soil in which the seed takes root, and grows, and yields a hundredfold—we who fight daily against the long, slow slide of the West from Catholicism into oblivion. We might argue that the now long and continuous failure of our own world has occurred only because we have not the courage and the constancy of Margaret Clitherow. But in so saying we would fail to notice that Margaret’s constancy was not rewarded by any visible Catholic renaissance even over several centuries.

The reality is that Our Lord seldom permits us to see the full fruit of our labors in His vineyard, and He may choose not to let us see any fruit at all, at least beyond the qualitative difference in our own souls. Once again we learn that Providence can be navigated only through Faith. We must embody Love, of course, but our consoling gift is precisely Hope, which is an unshakable confidence in God’s promises—and not in their tangible realization in the course of our own earthly lives. It may even, on occasion, be a warning sign if we see too much spiritual success which appears to arise from our own efforts, our own sacrifices.

But martyrs like Margaret Clitherow do remind us of just how little we have committed to the cause of Christ. Just as we know there is an unbreakable link between personal sacrifice and growth in grace, so too does St. Margaret challenge us to wonder about the extent and the purity of our sacrifices, which is to challenge the depth of our own soil, and its suitability for producing a rich harvest for the Lord.

In my case I would ask whether I spend more energy on being right than on being good. The two are inseparable, in that we cannot be good in doing what is wrong. But, alas, perspicacity and virtue are rarely proportionate. Even for those few who swim against the tide, it is typically easier to assert no falsehoods than to live in holiness.

York’s greatest woman, canonized by St. Paul VI in 1970 as one of forty martyrs of the English Reformation, was willing to sacrifice everything to achieve both. Today I can at least seek her intercession.

All comments are moderated. To lighten our editing burden, only current donors are allowed to Sound Off. If you are a current donor, log in to see the comment form; otherwise please support our work, and Sound Off!