Externals of the Mass

By Fr. Jerry Pokorsky ( bio - articles - email ) | Jan 19, 2026

When someone walks into a Catholic church, there are often different reactions. Regular parishioners feel at home. Visitors compare it—sometimes favorably, sometimes not—to what they know from their own parishes. Non-Catholics may feel anything from indifference to a quiet pull of attraction. That is not accidental. The externals of a church are meant to make the house of God feel like a home.

Our attention is immediately drawn to the altar and the tabernacle, usually beneath a prominent crucifix. On the altar, after the Liturgy of the Word, the Sacrifice of the Mass takes place—re-presenting the one redemptive Sacrifice of Jesus Christ. The crucifix reminds us that we preach Christ crucified and follow the way of the Cross. This is not meant to be comfortable or fashionable; the Cross directs us to the truth. The tabernacle, marked by a vigil lamp, holds the Blessed Sacrament—the consecrated Hosts. Jesus Himself is present there.

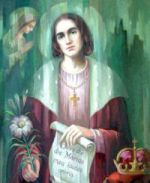

Statues, sacred images, and stained glass fill our churches. Despite a common misunderstanding, Catholics do not worship statues or Mary. Sacred art is incarnational. We are body-and-soul creatures, and visible reminders—like a photograph of someone we love—help keep us connected to spiritual realities we cannot see.

Catholic worship grows out of Jewish worship. In synagogues, the sacred scrolls of the Torah are kept in a place set apart. Catholic tabernacles serve a similar purpose, except that what is kept there is not a text but the Living Word—Jesus Christ—present under the appearance of bread. The reserved Hosts are used when Communion is needed at Mass or when priests bring the Eucharist to the sick and homebound.

Candles carry a warm symbolism. Jesus is the Light of the world. The wax represents His humanity, the flame His divinity, and the wick the union of the two natures—true God and true Man.

The altar is no longer used for repeated sacrifices. As the Letter to the Hebrews teaches, Jesus offered Himself “once for all.” That sacrifice is never repeated. Instead, at Mass, one Sacrifice is made present in an unbloody way, just as Jesus commanded at the Last Supper when He said, “Do this in memory of me.” Bread and wine—the work of human hands—become the means by which we encounter the Sacrifice of our Redemption.

The priest’s vestments help us understand his role. The white alb recalls baptismal purity. The cincture, a liturgical belt representing spiritual strength, reminds him of discipline and readiness. The stole signifies priestly authority. The chasuble, worn over all the vestments and changing with the seasons, represents Christ Himself. At Mass, the priest does not act in his own name but, by the graces of his ordination, in the Person of Christ. Even when a validly ordained priest is personally unworthy, he remains God’s instrument, and Jesus truly becomes present on the altar.

The chalice is often veiled during the Liturgy of the Word, recalling the curtain that once hid the Holy of Holies in the Temple. When the veil is removed at the Offertory, the gesture recalls how that curtain was torn at Christ’s death, opening access to God through Him.

Many churches include a Communion rail. The rail highlights the holiness of the sanctuary while still allowing the faithful to approach reverently and receive the Lord.

The prayers of the Mass have rich theological precision and hand down the faith through generations. Sacred music, especially chant, is not entertainment but prayer. As the saying goes, those who sing pray twice. Our prayers rise to the heavens with the smoke of incense. The bells stir us from our slumber and direct our attention to sacred priorities.

The distinction between the sanctuary and the nave (where the congregation assembles) reflects the complementarity of men and women in communion. “God created man in his own image; in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” (Genesis 1:27) At Mass, Christ the Bridegroom comes to meet His bride, the Church. He is the one mediator between God and man. His priests serve as friends of the Bridegroom, acting on His behalf.

Through baptism, we become members of God’s household—children of the Church. During Mass, Holy Mother Church feeds her children with the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of Jesus. At the end of Mass, we are sent forth to live what we have received.

A Catholic church is more than a building. Wherever the vigil lamp burns, reminding us of the Real Presence of Jesus, the house of God is a home. From His home, we are sent to proclaim Jesus, who made peace through the blood of the Cross and leads us to salvation.

All comments are moderated. To lighten our editing burden, only current donors are allowed to Sound Off. If you are a current donor, log in to see the comment form; otherwise please support our work, and Sound Off!