Those Amazing Cappadocians

by Boyd Wright

Talk about family values! Imagine a devoted husband and wife who raised nine children, four of whom would become saints — along with the couple and the children's grandmother. Imagine an older sister who fired her brothers with such faith that they energized Christian beliefs, forged new concepts in theology and laid a lasting foundation for monastic life.

That's the bare-bones story of a fourth-century family that grew up in Cappadocia in Asia Minor and so became known to history as the Cappadocians. (Now a part of Turkey and then a province of the Roman Empire, it was a land of rugged mountains, wild beauty and flourishing Christianity.)

The matriarch of the family was Macrina (the Elder), famous for piety. Her daughter, Emmelia, a great beauty and equally pious, married Basil, a rich lawyer and landowner. The young couple gave much of their fortune to the poor and became so beloved that folks said they performed miracles.

Their first daughter, Macrina (c. 327-379), was named for her grandmother. The child was only 12 when her intended husband died. Then and there she decided to devote her life to Christ. Such was her personality that she became the driving spiritual force behind all her siblings.

Her first brother, Basil (c. 329-379), named for his father, showed little sign of the family tradition of holiness, much less of the service to God that would one day earn him the title St. Basil the Great. As a young man, he received a first-rate education, studying five years in Athens.

Back home, he began a successful worldly career, teaching rhetoric and practicing law in Caesarea, the region's capital. But Macrina sensed something missing from her brother's life. She even accused him of "being puffed up beyond measure with the pride of oratory."

He ignored her.

Then tragedy struck. Naucratius, the next son, died suddenly. Basil, overcome by grief, found solace only in sitting at the feet of his sister to learn her secret of Christian tranquillity. Macrina had established a small community for Religious women on the family estate, and she persuaded Basil to do the same for men.

Basil at once showed the energy and thoroughness that would make him famous. Before founding his own group, he set out on a trip to discover how other godly communities lived. He wasn't satisfied until he had traveled through Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia.

Mostly, he met individual hermits living alone in caves and huts in the wilderness, disorganized, undisciplined, each struggling to find God in his own way. Basil came home convinced that the system Macrina had started for women would work for men, too — a community based on obedience where like-minded souls could renounce the world and together dedicate their lives to the Lord.

Basil picked a spot not far from the family home and slowly built his community. It became so successful that he expanded its rules as a model for similar groups everywhere. Here again we see his genius for thoroughness. One set of regulations became known as the Shorter Rule. It had only 55 articles. His Longer Rule contained 313.

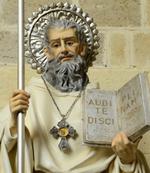

The rules served as a blueprint for a new monasticism, one based on spiritual strength and social works. What kind of man could induce others to follow this labyrinth of laws? Pictures of Basil show a massive figure, bull-headed and black-bearded with heavy eyebrows and a stern visage. His must have been a commanding presence, a personality to reckon with. But we know another side — little kindnesses to his monks, generous letters to those who sought his help, abiding loyalty from his followers.

Basil might have been happier cloistered in his community, but duty called him elsewhere. Cappadocia became engulfed in imperial and ecclesiastical quarrels. Then came natural disasters: earthquakes, drought and famine. Selflessly, Basil launched his talents into the wider arena, organizing relief and building hospitals and churches. He allowed himself to be named a bishop, and at age 40 was elected metropolitan of all Cappadocia.

Now Basil had to contend with heretics within his Church and with interference by Roman authorities. To bolster his position, he appointed a number of his supporters to bishoprics. Perhaps his most difficult task was to get his younger brother, Gregory (c. 331-394), to accept the see of Nyssa.

Gregory didn't want to be a bishop. Unlike Basil, this brother had not studied in Athens. He had stayed home and probably was tutored by Macrina. Certainly he absorbed much of her piety and applied it in his own way.

Basil was outgoing, dynamic; Gregory immersed himself in contemplation. He was slender, soft-spoken, ascetic. He wrote a life of Moses and long works of devotion steeped in mysticism. He married a wife said to be beautiful, and when she died, he joined his brother in monastic retreat.

Reluctantly, Gregory rallied to Basil's cause and accepted appointment as bishop. He mourned his consecration as the most miserable day of his life. He proved the exact opposite of his superbly organized brother and allowed imperial enemies to trump up charges of embezzlement. He had to go into hiding, and he always called this a happy time.

Then a new Roman emperor came to power, and poor Gregory had to go back to being a bishop. Bravely he stuck to his duties and proved a strong right hand for his brother.

Metropolitan Basil, whom people were already calling "the Great," had to talk another follower into donning bishop's robes. This was another Gregory — Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 330-390), who — though not a family member — would become the fourth of Christianity's famed Cappadocians.

Basil and this Gregory became fast friends when both were students in Athens. Gregory also came from a wealthy Cappadocian family. After the university, he too joined Basil in retreat. If Basil proved a mover and a shaker and Gregory of Nyssa a contemplative, the temperament of Gregory of Nazianzus fell between them. In him private and public life always warred. He was a gifted poet and sought seclusion to write, but he was an even greater orator, and came to find he could serve God best by preaching.

This Gregory didn't look like Basil either. He was small and frail with a high-domed forehead. Late in life he seemed shrunken by years of fasting. Fellow students from Athens remembered that Basil never yielded in debate, while Gregory always found an honorable compromise.

Gregory of Nazianzus also made a fuss when Basil, for political reasons, urged him to become a bishop. Eventually he accepted and, like Gregory of Nyssa, became a stalwart lieutenant for Basil, keeping political foes at bay, battling heretics and spreading orthodoxy throughout Cappadocia.

So what is the lasting legacy of these Cappadocians: Macrina, Basil and the two Gregorys? They did far more than fight the political wars of their time and place. Together they charted a whole new system of theology. Some say we owe as much to these three Eastern Fathers (and, it might be said, one "Mother") as the Christian West later in that century came to owe to St. Augustine of Hippo.

Basil died at age 50 at the height of his powers, and the two Gregorys carried on his work. A younger brother, Peter, became bishop of Sebastea, and he, too, must have helped. Peter was to become that generation's fourth saint.

That same year saw the death of Macrina. Before the end, Gregory of Nyssa hastened to her cell in the convent. For hours brother and sister talked quietly, sharing family confidences for the last time.

Gregory tells us that they agreed on a final theory: "Life, and honor, and grace, and glory, and everything else that we conjecture was seen in God."

Just before she died in his arms, Gregory asked a last question: What is the purpose of life? Macrina's answer spoke for all the members of that amazing Cappadocian family. She replied: "Love."

This item 4023 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org