Coming Soon to Your Parish

In Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh’s haunting novel about Catholic aristocrats in 1930s England, Rex Mottram, Julia Flyte’s crass, spiritually tone-deaf fiancé, seeks to become a Catholic in order to gain acceptance in her world. Rex neither knows nor cares anything about eternal truth. He means to listen without judgment and agree to everything, just to win the approval he wants, swiftly.

After a few meetings with Rex, Father Mowbray, a priest famed “for his triumphs with obdurate catechumens,” expresses concern to Lady Marchmain, Julia’s devout mother.

“I shall be dead long before Rex is a Catholic,” he said…. “The trouble with modern education is you never know how ignorant people are.…these young people have such an intelligent, knowledgeable surface, and then the crust suddenly breaks and you look down into depths of confusion you didn’t know existed. Take yesterday.

“He’d learned large bits of the catechism by heart, and the Lord’s Prayer, and the Hail Mary. Then I asked him as usual if there was anything troubling him, and he looked at me in a crafty way and said, ‘Look, Father, I don’t think you’re being straight with me. I want to join your Church, but you’re holding too much back.’

“I asked what he meant, and he said, ‘I’ve had a long talk with a Catholic—a very pious, well-educated one— and I’ve learned a thing or two. For instance, that you have to sleep with your feet pointing East because that’s the direction of heaven, and if you die in the night you can walk there. Now I’ll sleep with my feet pointing any way that suits Julia, but d’you expect a grown man to believe about walking to heaven? And what about the Pope who made one of his horses a cardinal? And what about the box you keep in the church porch, and if you put in a pound note with someone’s name on it, they get sent to hell? I don’t say there mayn’t be a good reason for all this,’ he said, ‘but you ought to tell me about it and not let me find out for myself.’”

“What a chump! Oh, Mummy, what a glorious chump!” shouts Cordelia, Julia’s impish little sister. “Oh, Mummy, who could have dreamed he’d swallow it? I told him such a lot besides. About the sacred monkeys in the Vatican—all kinds of things!”

The kind of religious education practiced by Cordelia Flyte is now called “faith-sharing,” “faith formation,” or “adult faith-formation.” Its style, familiar to veterans of RCIA or Renew I and II programs, is also the heart of “whole community catechesis.” It may well be the wave of the catechetical future.

“Faith sharing” means gathering the relevant community in jolly social groupings and encouraging them to tell each other what they believe. No one is permitted to object to another’s belief, or to tell anyone else what he ought to believe; that would be "proselytizing," which is oppressive. By contrast, simply talking of one’s “faith journey” is liberating. However uninformed one’s opinion might be, participants are assured that it serves “to further the reign of God.”

Recognizing the Desolation

Two related subjects dominated the discussion when some 800 members of the National Conference for Catechetical Leadership (NCCL) met in Albuquerque in late April for their 2004 conference. The first item was a national catechetical directory, now being constructed by a committee of US bishops, to the distress of the NCCL. The second was a style of “whole community” religious education that seems headed for nationwide adoption, with NCCL’s blessing.

Initially, there seemed to be a refreshing whiff of honesty in the Albuquerque air. The theme for the gathering was “Spirit of Life in the Desert,” and in their reference to the "desert" the NCCL leaders were alluding not just to the local scenery, or to the recent clerical sexual scandals, but to the generally desolate state of the Church in the United States. This admission is significant, coming from an organization with official ties to the US bishops’ conference.

After 40 years of relentless propaganda about the marvels of “renewal,” this NCCL conference featured a very different message. Speaker after speaker acknowledged that no one in their programs today knows anything about the basic doctrines of the faith. Their students—and their students’ parents—live by the standards of a decadent secular society.

The religious-education establishment, it seems, no longer denies the blighted state of Catholicism. Yet no NCCL speaker audibly admitted having had a hand in causing the blight. Parental apathy was blamed, along with rapid social change, the hectic pace of contemporary life, the decline of Catholic culture and the loss of Catholic identity, and even the “backlash” from traditionalists.

From a revealing pre-conference workshop to Father Richard Rohr's ambiguous closing address, attendees were urged to face the reality of religious illiteracy, and to undertake corrective programs. In his homily at a conference Mass, Archbishop Michael Sheehan of Santa Fe exhorted catechists to teach students “faith facts” in addition to providing the kind of experiential reflection that has ruled in the field for decades.

Indeed, "faith facts" and "Church traditions"—words anathematized 40 years ago by catechetical theorists—are the current catch phrases in the realm of religious education. Catechetical authors and publishers are jostling each other in their eagerness to offer programs and tactics promising to restore Catholic identity by involving entire parish communities: grandparents, parents, and catechists, as well as children.

Mixed News

Among the most illuminating of conference events was a workshop on the unfinished National Directory of Catechesis being drafted by the US bishops' conference (USCCB). It was assessed at a pre-conference workshop for diocesan directors of religious education (DREs) by Dr. Michael P. Horan, an assistant professor of religious education and pastoral theology at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, and a current member of NCCL’s representative council.

While Horan’s stated subject was not catechesis through “faith sharing,” he is linked with that trend by his collaboration in Exploring the Catechism, a 1994 book by Dr. Jane Regan of Boston College. Regan, an early, ardent and prominent advocate of “adult faith formation,” insists not only that “the community (is) the agent of catechesis,” but also declares that “the content of catechesis is not something we give or present to the learners, but rather a reality that we attempt to live out and incarnate with the life of the community.”

There was no hint of contrition for the present malaise among Catholics in Horan’s heated defense of “the modern catechetical movement in the post-conciliar era.” In Horan’s view, its history is glorious. A 1970s alumnus of Catholic University’s infamous Religious Education department, he is still enamored of the spurious "vision of Vatican II" prevailing there at the time. Starting with a derisive reference to the “chilling” Baltimore Catechism, he reviewed the Vatican II call for a catechetical directory that would present a broad new vision, “looking at the human situation of the Church, including the best ecclesiology, the best sociology, the best personnel, the best resources” of the council."

Sharing the Light of Faith, the catechetical directory published in 1979 for the US, marked the move away from knowledge-based catechesis to a view that “faith is relational”—that is, the view that faith is not a matter of believing truths but of becoming part of a community. Horan quoted Richard Reichert’s description of the shift in catechetical focus from the pre-conciliar goal of “teaching the faith” to the post-Vatican II goal of building relationships. In Renewing Catechetical Ministry, Reichert explains: Prior to the council the goal of catechesis was to help children become loyal, obedient, and conscientious members of the institutional church by providing them with a solid education in the truths of the faith. The council, on the other hand, initiated a shift toward understanding the goal of catechesis as one of forming disciples of Jesus who would be both willing and capable of participating in a community committed to proclaiming and promoting the reign of God in today’s society.

In the chaos after the council, similar rhetoric about community was often heard from newly professional directors of religious education. But at the level of the students, this discussion of community was a secondary matter; far more obvious was the fact that content simply vanished overnight. Almost nothing was taught anymore but indeterminate kindness, and the “compassionate” leftist political views of the new bureaucrats heading diocesan and parish programs, and of catechetical textbook authors, many of whom, like Thomas Groome, Janaan Manternach, and Carl Pfeifer, were (or would soon become) ex-priests and ex-nuns.

A "Peak Experience"

Beliefs and attitudes can be changed with astonishing speed by a changed curriculum. Soon most Catholic children in the US were learning that their country is to blame for the world's poverty. Catholic high-school students, especially, were led to believe that the Church demands pacifism and prohibits capital punishment (neither of which is true). As feminist ideology captured DREs, children learned (again falsely) that there were women priests in the early Church, and probably will be again. With the fad of "Creation Spirituality" they learned that the planet Earth is Christ for our time.

What students did not learn was clear Catholic doctrine. They did not even learn that Jesus is more than man, that he is true God. Or if they learned that he is divine, they were told that he didn’t know it.

As defined dogma slid down the Memory Hole, Catholic students ceased believing in anything larger than secular culture. The great majority stopped coming to religion class entirely. Today those who still attend are apt to be dropped off for class by parents who neither take them to Sunday Mass nor attend themselves.

Parish DREs rarely meet the saving remnant of passionate Catholic believers, because students from these families are unlikely to be enrolled in parish religion classes unless their parents can find no other way for them to receive the sacraments of First Communion and Confirmation. The rest of the time they are taught at home, frequently from the Baltimore Catechism.

But in Horan’s opinion, the chief lesson of Sharing the Light of Faith was that “the process is more important than the product.” During public consultations on the four drafts of the document, some 90,000 Catholics submitted recommendations to the drafting commission. It was, said Horan, a “peak experience for catechesis.” Recalling the openness of a meeting room “swathed in newsprint” as participants offered suggestions, one woman sighed: “That was a whole different world."

Then in 1997 Pope John Paul II approved a new General Directory for Catechesis, and soon a committee of US bishops began constructing a new National Directory of Catechesis. Horan sees nothing to cheer about in that development. He held up a clandestine copy of the draft, and described his dismay upon realizing that the USCCB staff and the relevant committee of bishops have composed it without consulting NCCL. Bishops have offered more than 1,000 amendments, amounting to nearly a third of the text, and every one is automatically accepted unless it duplicates an earlier one. Sixty-four of the first 215 amendments were submitted by just two bishops, he said: Fabian Bruskewitz of Lincoln and Raymond Burke of St Louis. Four other bishops, including Thomas Doran of Rockford and Cardinal Bernard Law, late of Boston, accounted for most of the rest.

Listing the changes that trouble him most, Horan noted that the term “ecclesial community” was amended to “Church.” References to “deacons and their wives” became simply “deacons,” and “lay ecclesial ministers” became “seminarians.” Archbishop Burke restored one paragraph previously cut in the consultation process, and replaced a reference to “the Holy Spirit working through the people” with the phrase “magisterial truth.”

“In other words,” sighed Horan, “we’ll be back to discussing the problem of ‘eternal’ truth.” The workshop audience groaned along with him.

Worst of all, Horan mourned, the uniquely democratic, multi-cultural American approach to catechesis is in danger of being forgotten, as the consultative process used in putting together the first directory has been lost in the second. At the insistence of Bishop Bruskewitz, references to the catechist’s task as one of “interpreting” tradition were changed to “understanding.” The Church, said Horan, is “at this time and place in a desert.”

Yet neither Horan nor the conferees conceded defeat. "The document is a tool, not an end in itself," one woman recalled. “The process is more important than the product.”

Horan agreed. “We have this movement on which to build.” The modern catechetical movement is the miracle of today, he said. Explaining how the National Directory of Catechesis grew out of the General Directory for Catechesis will furnish the occasion for a catechist to teach about Vatican II and the history of modern catechesis.

“The bishops said to stop interpreting tradition and begin to understand it. But the fact is, we are always interpreting,” Horan said. He continued:

We bring the document to the people, and raise the issues to people’s minds. Does a given translation support people’s experience or not? The document comes through us, the catechists.

“You’ve given me hope," a DRE told Horan. “We are the ones to do the interpreting. It’s gotta come through us.”

Horan nodded. “That’s an ideological struggle we will be having for many years.”

Changing Bishops' Minds

"Whole Community Catechesis" and "Generations of Faith" were buzz words at the Albuquerque conference, as they had been in February at both the mammoth Los Angeles Religious Education Congress and the East Coast Conference for Religious Education, in Washington, DC.

At an NCCL “breakout session” for diocesan DREs, catechetical authors, publishers' representatives, and a few religious education professionals, plugged new programs and materials. After “animator” Mary Kay Cullinan of Metuchen, New Jersey, led the reluctant audience in singing David Haas’ “We come to share our story,” speakers began an informal but revealing seminar.

- Bill Huebsch is the author of Whole Community Catechesis in Plain English, a 2002 product of heterodox Twenty-third Publications. He is also an advisor to RCL publishers, and is Harcourt Religious Publishers’ senior advisor on total parish catechesis. His boyish manner, on the religious education circuit where he is a frequent speaker, may distract listeners from noting how often he weaves threads of dissent into his addresses. Nevertheless, at NCCL’s forum, it was Huebsch who insisted that whole community faith-formation programs should include direct catechesis with texts that have been judged “in conformity” by the USCCB committee to oversee the use of the Catechism. Huebsch is a writer for Harcourt’s elementary level textbook series, Call to Faith, which does have the “conformity” ruling; perhaps that fact influenced his stand, or perhaps he wanted to reassure sincere DREs in the room of his orthodoxy. In any case, what he said was sound: “I favor using a completely approved text series. A child has a right to learn about Mary and the Rosary. We need a full, comprehensive, systematic presentation of the faith."

For conferees seeking to understand the new paradigm, Huebsch recommended both his own Whole Community Catechesis, and Horizons & Hopes: the Future of Religious Education, Thomas Groome’s new book from Paulist Press, with its foreword by Sister Edith Prendergast. Huebsh urged the diocesan DREs to read at least chapter two, by Jane Regan, who was “doing this 15 years ago in Minnesota parishes.” Holding the book up, he said, “Jane Regan’s brilliant chapter on adult faith formation is worth the price of the book all by itself.”

- John Roberto founded the Center for Ministry Formation in 1978, and served as its director until 2000. While at CMF he founded the Generations of Faith Project, developed it with funding from the Lilly Endowment, and now, as its director and project coordinator, conducts training workshops across the US for staffs at the growing number of parishes that are initiating the Generations of Faith program. Seven hundred parishes in 60 dioceses are already using GOF; 21 parishes in the Raleigh diocese signed on last December.

Unlike Huebsch, Roberto consistently argues against textbooks, citing such varied authorities as the General Catechetical Directory, #158 (“the community is proposed as the source, locus and means of catechesis”), and Maria Harris, (“the church is the curriculum, content, and catechist.”)

- A surprise panelist at the NCCL forum was Sister Edith Prendergast, RSC, director of the Los Angeles archdiocesan Religious Education Office and organizer of its notorious annual Religious Education Congress. She also spoke at the East Coast Conference in February this year, where Whole Community Catechesis was the sole topic.

Sister Prendergast’s chief contribution to the forum concerned tactics for persuading a bishop to embrace the new paradigm of catechesis: tell him the new model fulfills the prescription called for by #158 or #254 in the 1997 General Directory for Catechesis. Incorporate all diocesan ministries, too, she said; Los Angeles is including representatives from Religious Education, the worship office, the synod, and other archdiocesan ministries, in planning for whole community catechesis to start early in 2006.

Huebsch, who spoke at the Los Angeles Religious Education Congress in February, agreed that the key to acceptance is “informing, educating, changing bishops’ minds to accept the adult Church model. Many bishops don’t have them committed to memory.” The Los Angeles conference succeeds because catechetical leaders work with the bishops, he said. “I don’t think we can go forward without the bishops.”

“Generations of Faith has some of the same concerns,” agreed John Roberto. “Most bishops are concerned that we are taking the Church and making it the center of catechesis.” The tactic Roberto proposed to allay bishops' fears is to tell them that catechists are only fulfilling the directives of #158 of the General Directory for Catechesis. He went on:

Faith formation is event-centered, developed around the events of our shared life as Church. Faith formation demands a unified, life-long catechesis. Through events, we have a 6-year curriculum: the Church year of feasts and seasons, sacraments and liturgy, rituals and prayers, spirituality, justice, and service. Beliefs and practices for living as a Catholic emerge from the life of the faith community. The content emerges out of the event. A text is not the curriculum; the curriculum is the life of the Church. An introductory video for Generations of Faith offers colorful footage of cheerful intergenerational groups, with adults mingling, eating (food is always part of the event), chatting, and praying in parish centers and churches, while happy children construct craft projects or paint primitive symbols, dramatize Bible stories, or sing in choirs. These parishes appear to offer the kind of warmly welcoming ambiance Protestant converts often say they keenly miss when they become Catholics.

In place of weekly catechism classes for children, these programs feature a single monthly assembly or “faith festival,” where parishioners of all ages gather for a meal, see a dramatic presentation of a Bible story, hear an address about a community problem, or celebrate the event of the month (cited as examples were Advent, Lent, Thanksgiving, and Kwanzaa). After a general prayer service, all break into peer clusters for discussion, singing, or art projects. The entire group joins together for closing prayer. On their way out, participants pick up take-home materials that will reinforce the evening’s theme, help prepare for the next event, or suggest some form of community service or political activism.

Illiteracy and Alienation

Because the problems of religious illiteracy and alienation are authentic and acute, the presentation was attractive even to skeptical listeners, daring to hope that it might mean the beginning of real change. Generations of Faith is endorsed by NCCL as an initiative to revitalize American Catholic life. In the right hands, with sound doctrinal instruction as its centerpiece, the social component of whole community catechesis certainly could enrich parish life. There is enormous hunger among the laity to hear and understand the eternal truths and moral teachings that neo-modernists in the catechetical movement long ago jettisoned.

But the Generations of Faith film, like other “whole community catechesis” literature on display, skims over questions about specific doctrinal content. (“The parish is the content.”) Detailed examination of the GOF materials and their sources reveals alarming resemblances to the hollow Renew I and II and RCIA projects that engage the laity in uninstructed, heterodox "faith-sharing" without authentic “indoctrination” to let them know what the Church really teaches. It might be possible to integrate solid catechesis into GOF’s lively social method, but that seems to be entirely optional.

The philosophical grounding of an educational program is revealed in its origins, references, footnotes, and bibliographies. Bill Huebsch said that whole community catechesis grew out of the 1968 Medellín conference of Latin American bishops, who launched church groups into liberation theology by way of basic Christian communities.

NCCL’s forum outline about GOF credits the contributions of a feminist former nun Maria Harris, and such other “foundational thinkers,” as Anglican John Westerhoff; Sister Catherine Dooley, OP, of the religious education department at Catholic University of America; and progressive Francoise Darcy Berube, whose 1996 book, Religious Education at a Crossroads exhorts educators not to “turn back in fear” to the catechism model of the rigid “good old days.”

Listed beside the General Directory for Catechesis and various USCCB documents, among course texts and resources for a Certificate in Lifelong Faith Formation to be offered in January 2005 by the Center for Ministry Development, along with Bill Huebsch and Maria Harris, are the names of still other architects of the specious “catechetical renewal”: Sister Kathleen Hughes, RSJC, James Davidson, William D’Antonio, Jane Redmont, William Shannon, Loughlan Sofield, ST. These professionals are deeply implicated in the present decline, yet they still seem certain they’ve been heading in the right direction these forty years. Why haven’t they arrived at their destination, then? There simply hasn’t been time yet, they explain.

Bernard Lee, SM, is director of the Institute for Ministry at Loyola University, New Orleans, and a member of the Call to Action Speakers Bureau. In his presentation on Small Christian Communities, he said that “reform” councils like Vatican II produce a backlash. He counseled: “Until the backlash is out of your system, you can’t really get on with the reforms.”

At the banquet where he accepted NCCL’s 2004 Catechetical Award, former Christian Brother Gabriel Moran (whom NCCL correctly credits with “reshaping the field of religious education”) said turmoil is to be expected after a council, and new building cannot begin until the resistance is cleared away. Moran is near the end of his career, and his wife Maria Harris is now too ill to travel; they do not expect to see the triumph of their lifework. But Moran still thinks triumph will come, despite general recognition by their peers that religious education has been devastated.

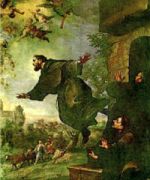

It seems odd that NCCL chose to present its award to a man who bears so much responsibility for the devastation. It is rather like elevating a horse to the college of cardinals.

Donna Steichen is the author of Ungodly Rage: The Hidden Face of Catholic Feminism, and Prodigal Daughters: Catholic Women Come Home to the Church, (both from Ignatius Press). She writes from Ojai, California.

This item 6470 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org