Make your gift today!

Help keep Catholics around the world educated and informed.

Already donated? Log in to stop seeing these donation pop-ups.

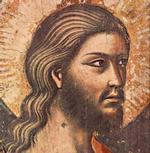

St. Basil The Great

This Saintly Sketch is the first of three that will feature the Cappadocian Fathers: St. Basil, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, and St. Gregory of Nyssa.

Different saints have administered to different spheres of the Church's life. Some saints made significant contributions to the spiritual life, like St. Therese of Lisieux. Some saints are known for their intellectual contributions, like St. Augustine. Some saints are remembered for their pragmatic ability to handle God's earthly affairs, like St. Gregory the Great. Many saints have penetrated two of these areas (like Gregory the Great, the great administrator and doctor of the Church). But only a few saints have made a significant mark in all three areas.

St. Basil the Great is one of them.

Early Life

Basil was born in 329 in the big city of Caesarea (population of about 400,000), in the region known as Cappadocia, which is located in eastern Asia Minor (the middle of modern Turkey). His father was a wealthy lawyer with extensive landholdings. Both of his parents were devout Christians whose immediate ancestors were converted to the faith by St. Gregory Thaumaturgus, the "Wonderworker," who converted large portions of Asia Minor in the third century.1 Basil's father was so famous for his devotion that it was widely believed he could perform miracles; Basil's grandmother, St. Macrina the Elder, was a fiercely devout woman who told stories about the "old days" of Christian persecutions. In all, Basil's immediate family produced five saints.

Basil received his early education from his father and the pagan teacher of rhetoric, Libanius. At about age 21, he enrolled at the University of Athens, the greatest university of the day, where he studied for five years. When he returned to Caesarea, he became the chair of rhetoric at the University of Caesarea and was on course for a satisfying career as a professor and lawyer.

But his sister and brother changed that. One through her words; the other through his death.

Monk And Administrative Assistant

Shortly after starting his professional career, the upwardly-mobile Basil was castigated by his older sister, Macrina the Younger. She disliked his ambition and accused him of being "puffed up beyond measure with the pride of oratory." Unfortunately, her words didn't seem to affect Basil much.

But then his brother, Naucratius, died. Naucratius was a highly gifted man: handsome, strong, agile, intelligent, and touched with God's spiritual grace. He died in a hunting accident, and Basil was thunder-struck. He went to Macrina and sat at her feet, learning the way of Christian renunciation and virtue.

With a renewed devotion in his heart, Basil left on a trip to tour the great monastic foundations in Palestine, Syria, and Egypt, arriving in Egypt shortly after the death of St. Antony the Great. Although he admired the life of the anchorites, he didn't trust their isolated lifestyles, which often led to spiritual pride, fierce individualism, and disobedience to the Church. He returned to Cappadocia with plans to imitate the desert fathers, but in a community, not in isolation. He set up a monastery and stayed there with a handful of men.

Basil's monastic pursuit testifies to both his pragmatic and his spiritual insight. He busied himself with the practical concerns of monastic life, like maintaining the facilities and managing finances, while still primarily emphasizing the spiritual purpose of monastic living. This combination of pragmatism and spirituality is well evidenced by his (arguably most famous) work, the Longer Rules for monastic life. The lengthy Rules, consisting of 55 detailed articles, became the model for Eastern Christian monasticism and greatly influenced St. Benedict, the father of Western monasticism.

The Rules emphasized three elements that are found in monasticism to this day: Obedience to the superior, manual labor, and charity for the poor. Obedience was the cornerstone of Basil's monastic vision because it was the characteristic that set communal monasticism apart from — and protected it against — the individualistic pursuits of the Egyptian anchorites. Basil emphasized manual labor because Jesus (the carpenter) and the earliest generations of Christians were manual laborers. He also emphasized it for practical reasons (like earning money for food) and for spiritual reasons (working with the hands is good for the soul). Finally, Basil emphasized charity for the poor by teaching that charity fulfills man's highest calling.

Basil stayed in the monastery five years before answering the call of Eusebius, Bishop of Caesarea, to be his administrative assistant. Basil proved an excellent administrator that the Bishop relied upon extensively. Basil also proved to be a caring administrator. During his administration, for instance, Cappadocia suffered a severe drought that devastated the poor people of Cappadocia. Basil labored endlessly to relieve their suffering. He blasted the rich hoarders "who let their wheat rot, while men die of hunger," asking, after graphically describing the horrendous death of starvation, "What kind of punishment, do you think, is deserved by a man who passes the hungry without giving them a sign?" He exhorted the rich to share their blessings, then sold the land he had inherited from his lawyer father and gave the money to the hungry. He tenderly cared for the poor, washing their dry dusty feet and comforting them.

Although he was an excellent administrator, Basil would have preferred to return to the monastery. But when Eusebius died in 370, Basil was compelled to accept the position of Bishop in order to fight against the heresy of Arianism. Both Valens, Emperor of the East, and Demophilus, Patriarch of Constantinople, were Arians, and the Eastern Church was in dire risk of falling completely to Arianism. It seemed like every believer in the East was looking to the tough-minded Basil to save orthodoxy.

Arian Opponent

The bitter, disingenuous, and dangerous nature of heresy is well highlighted by Arianism, a heresy that denied the full divinity of Christ. Its creed was repeatedly rejected by Church councils and the faithful, but the Arians persistently tried, through imperial intrigue and coercion, to pry it into the Church. When Valens came to the Byzantine throne in 364, he demanded that the faithful accept the Arian-tainted creed that had been formulated at the Council of Rimini.2 The "Creed of Rimini" implicitly denied Christ's divinity by remaining silent on the matter, a ploy the Arians adopted because they had learned by experience that explicit Arianism would always be rejected.

Basil labored constantly and preached effectively against Arianism and the Creed of Rimini. In order to weaken Basil, Valens divided Caesarea into two provinces, thus slashing Basil's jurisdiction and reducing the number of bishoprics in his territory. In response, Basil elevated villages to bishoprics (including the little villages of Nyssa and Nazianzus, compelling his little brother and best friend, both named Gregory, to become bishops there against their wills).

It didn't take Valens long to take more direct action against Basil. In 372, Valens' zealous Arian servant, Modestus (the "Count of the East"), came to Caesarea and summoned Basil. Basil — emaciated from his asceticism but mentally rigorous — came. Modestus shouted at him: "Basil, how dare you defy our great power? How dare you stand alone? Everyone else has yielded, and you alone refuse to accept the religion commanded by the Emperor." After Basil showed no recalcitrance, an exchange took place that is recounted in every biography of Basil:

Modestus: What, do you not fear my power?

Basil: What could happen to me? What might I suffer?

Modestus: Any one of the numerous torments which are in my power.

Basil: What are these? Tell me about them.

Modestus: Confiscation, exile, torture, death.

Basil: If you have any other, you can threaten me with it, for there is nothing so far which affects me.

Modestus: Why, what do you mean?

Basil: Well, in truth confiscation means nothing to a man who has nothing, unless you covet these wretched rags, and a few books: that is all I possess. As to exile, that means nothing to me, for I am attached to no particular place. That wherein I live is not mine, and I shall feel at home in any place to which I am sent. Or rather, I regard the whole earth as belonging to God, and I consider myself as a stranger or sojourner wherever I may be. As for torture, how will you apply this? I have not a body capable of bearing it, unless you are thinking of the first blow that you give me, for that will be the only one in your power. As for death, this will be a benefit to me, for it will take me the sooner to the God for Whom I live, for Whom I act, and for Whom I am more than half dead, and Whom I have desired long since.

Basil's words are a testament to the truth that the meek inherit the earth. After this exchange, Modestus largely left him alone, and the Emperor Valens never pushed matters to a conclusion with Basil again.

The Theologian

Basil also fought against Arianism through his learning. All his extant dogmatic treatises are devoted to the overthrow of Arianism, including one of his earliest works, Against Eunomius, a book dedicated to fight the particularly-strident Arian views of Eunomius, who denied that Christ had any divine substance whatsoever. His fight against Arianism also led him to write a work, On the Holy Spirit, which has led some to refer to him as a theologian of the Holy Spirit.

Basil's contribution to the development of Trinitarian and Christological doctrine was immense. Following Athanasius' success at the Council of Nicaea in 325, there were still legitimate questions about orthodoxy's doctrine on the Trinity and Christ's nature, and these questions led to misunderstandings and controversies. Basil helped clarify matters by being the first to insist that God consists of one substance but three persons. His theology of the Trinity and Christ's nature would lead to the formulation at the Council of Constantinople in 381 and ultimately pave the way to the final definition adopted at the Council of Chalcedon in 451.

In addition to his important contribution to Trinitarian and Christological doctrine, Basil wrote on an array of other topics, including creation, morality, books of the Old Testament, canon law, liturgy, the Eucharist, and confession.

Early Death

Basil suffered from physical ailments all his life, which were exacerbated by his ascetic life.3 At the age of 41, his appointment as the Bishop of Caesarea was resisted by some people who thought him too physically weak to serve. At the age of 43, he said "my body has failed me so completely that I can make no movement at all without pain." At the age of 46, he lost his last tooth. At the age of 50, he was dead, so worn from administrative, ascetic, and intellectual pursuits that his corpse looked like a man who had died of old age. And this is fitting, for he did more in each of the three spheres of human existence — the physical, mental and spiritual — than most men who live twice as long do in the three spheres combined.

Eric J. Scheske is an attorney in Sturgis, Michigan, where the small town practice of law leaves time for reading and writing.

End Notes

1 As an interesting aside, St. Gregory Thaumaturgus was also the first recorded person to receive a vision of the Virgin Mother.

2 The Council of Rimini, held in 359, was an invalid Church council because the Pope, Liberius, was neither consulted about, nor represented at, the Council.

3 He especially suffered from a problem with his liver. When, at another time, Count Modestus flashed a sword at Basil and threatened to cut out his liver, Basil replied, "Then I shall be grateful to you . . . Take it, and you will relieve my suffering."

© Ignatius Press 2000.

This item 4445 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org