Holy Orders - Part I

by Benedictine Monks of Buckfast Abbey

Priests may sometimes feel inclined to imagine that the Pontificale Romanum is a book, which holds but scant practical interest or utility for them. The very title of the book seems to restrict its use to those in whom resides the fullness of the priesthood. True, the Pontificale is indeed the bishop's own manual, containing as it does the formularies of rites and Sacraments the administration of which belongs to him exclusively. However, for that very reason the book is of interest to simple priests also, for it was amid the wonderful ceremonies and prayers found in its pages that they received their mysterious powers.

The Pontificale Romanum, as a distinct liturgical book, is of comparatively recent origin. During many centuries the matter, which forms its text was scattered in divers sacramentaries and ordines. It was in the eleventh century that the formularies used at episcopal functions were first collected in a separate volume, and the first printed edition of the Pontificale appeared in 1485 during the pontificate of Innocent VIII, its editor being the famous liturgist, Burchard. For the sake of uniformity throughout the Latin Church, not only as regards the Office and Mass but likewise in respect to episcopal functions, Clement VIII published the first official edition of the Pontificale in 1596. The Bull Ex quo in Ecclesia Dei, which is printed at the head of this edition, forbids the use of any other formulary.

The book is divided into three sections: the first consists of the ritual to be used for the blessing and consecration of persons; the second part is made up of formularies for the consecration of material objects and that of places; the third section lays down the manner of performing certain functions in the administrative life of the Church, such as the celebration of synods, episcopal visitations, and so forth.

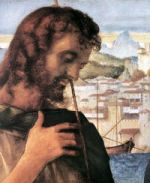

The first part of the book is the one that concerns every priest in a most intimate manner, for it was by the rites there set down that he received in succession the various "orders" which convey to him the supernatural character with which he is adorned. As we ponder the sonorous phrases of its noble prayers, there comes over us a feeling akin to that with which the scion of a noble house reads the charter by which an ancestor of his was at one time ennobled, for of all nobilities there is none comparable to that which is conferred upon those with whom Christ deigns to share His own eternal priesthood. "The priest bears the very form and appearance of Christ (Sacerdos Christi figura expressaque forma est)," says St. Cyril of Alexandria (Migne, P. G., LXVIII, col. 882).

A study — even if necessarily a brief one — of the rites and ceremonies of ordination is most instructive, for the liturgy of the Church is nothing if not illuminating, and we learn much about the true nature of Holy Orders by studying the various steps by which we advanced in the sanctuary, until the moment came when we too heard, more even with the heart than with the ear, the echo of that sublime consecration when, in the splendors of uncreated holiness before the day-star, the Father ordained His beloved Son a priest forever according to the order of Melchisedech.

The Tonsure

The heading of the first rite, which we meet as we open the Pontificale is: De clerico faciendo. The prayers and ceremonies of the rite sufficiently explain its meaning and purpose. The tonsure is not a real order — that is, it confers no specific sacred power to the person who receives it — but it is a ceremony by which the Church marks off from the rest of the faithful those whom she calls to the service of the altar. From the moment of his tonsure the candidate becomes a cleric, and ceases to be a layman.

At the beginning of His public life our Lord gathered around His Person certain men in order to give to them what might be called a course of special and intensive training. Amid the intimacies of daily intercourse He imparted to them that knowledge, and raised and brought to maturity those virtues, which were to make of them the worthy heralds of the glad-tidings. He Himself bears witness to the results achieved: "To you is given to know the mystery of the kingdom of God, but to the rest in parables" (Luke, viii. 10). Here we have a clear-cut differentiation: "to you ... to the rest." Subsequently our Lord surrounded this inner circle of friends and Apostles by an outer ring of seventy-two disciples.

From the first we thus find a distinction among the followers of "Christ — those who were only disciples and those to whom certain extraordinary powers were granted. Thus, St. Luke speaks of those who "from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word" (Luke, i. 2). In the Acts two functions are said to be the real task of those who were at the head of the body of believers: "We will give ourselves continually to prayer and to the ministry of the word" (vi. 4). By prayer is meant not merely their personal intercourse with God, but likewise the official worship of the New Law. The imposition of hands, with prayer, is the original and essential rite of ordination (Acts, xiii. 3, 4).

A word had to be coined to designate the state of those who were chosen from among the people to be their teachers and guides. In the second century Tertullian already (De idol., vii) speaks of "the ecclesiastical priestly order" (ordo sacerdotalis ecclesiasticus). As opposed to the state of the faithful ( laikos, laicus), that of the "elders" (presbyters) is called klerikos (clericus). The word is singularly appropriate, for the sacred ministers are chosen, if not by lot (kleros), at least by a call from God, and on entering upon their sacred career the candidates choose God as their lot or inheritance. Already St. Augustine and St. Jerome give this twofold meaning to the word: "I think they that have been ordained in the order of the ecclesiastical ministry have been called both clergy and clerics, because Matthias was chosen by lot" (Augustine, In Ps. lxvii). "Clerics are thus called because they are the lot of the Lord, or because the Lord Himself is their lot, that is, their inheritance" (Jerome, Ep. ad Nepot., cap. v).

Nor is a man enrolled in the priesthood of the New Law by the simple fact of birth, as was the case with the Levitical priesthood. Two factors come into consideration in this matter. On the one hand, the candidate must have an inward consciousness of a call from God, and, on the other hand, the Church must approve of him. But mere acceptance by the Church for the ministry does not by itself give to the candidate any spiritual powers: that is only done in virtue of ordination — viz., through the Sacrament of Holy Orders.

II

The tonsure does not come under the heading of the Sacrament of Holy Orders. It is more in the nature of a juridical act of the Church whereby she bestows upon the chosen candidate certain privileges belonging to the clerical state. From civilian jurisdiction the new cleric passes under that of the Church, so that, if the State were a truly Christian one, it would acknowledge the Church's right to be the sole judge of her ministers. The privilege of the Canon, as it is called, may be forfeited and the candidate may still be completely reduced to the lay estate; whereas, if he has received merely one of the minor Orders, he retains forever the spiritual power thus conferred on him. This fact is pointed out by the bishop at the conclusion of the ceremony: "Dearly beloved sons, take heed that today you have come under the jurisdiction of the Church, and that you have inherited the privileges of the clergy; be you therefore on your guard lest you lose them at any time by your misconduct." The origin of the tonsure is very obscure. There are those who would trace it back to Apostolic days. We may take it as certain that during the first centuries there was nothing either in dress or cut of the hair to differentiate between clerics and laymen. To act otherwise would have been a useless courting of persecution, even of death itself. All we know is that various canons of the first centuries forbid the clergy to bestow too much care upon their hair. From the fourth century onwards, however, we meet with instances of the tonsure. Monks and nuns cut off their hair and even shaved their heads to testify to their contempt of the world. In this they were soon imitated by the clergy. St. Jerome (In Ezech., cap. xliv) blames both those who carefully nourish their hair and those who shave their heads: he wishes the clergy to avoid both extremes by wearing their hair short "to show forth the modesty that should characterize a priest's outward appearance" (ut honestus habitus sacerdotum facie demonstretur). "Let a priest grow neither hair nor beard (Clericus nec comam nutriat nec barbam)," says Canon XLIV of the Fourth Council of Carthage.

There has been but little uniformity as regards the form of the tonsure, and medieval liturgists show their usual resourcefulness in their mystical interpretations of the various shapes it took. That it is essentially a symbol, is obvious. According to the Magister Sententiarum (IV Sent., Dist. XXIV), it is an emblem of spiritual kingship (ministri Ecclesiae reges debent esse). The Fourth Council of Toledo (633) prescribes the tonsure for all members of the clergy. It is to be made in such wise that, the top of the head being shaven, a crown of hair remains encircling the head (Canon 1441). The tonsure retained this shape throughout the whole of the Middle Ages. During a number of centuries it was not given by itself, but formed a necessary adjunct to the reception of the first of the minor orders.

III

The Council of Trent makes no mention of the tonsure when it enumerates the various Orders (Sess. XXIII, cap. ii), but holds it to be a preparatory step for the reception of Holy Orders, for it expressly forbids (cap. iv) the giving of the tonsure, unless there is a reasonable presumption that the candidate asks for it, not for the purpose of escaping from the jurisdiction of secular tribunals, but with a view to dedicating himself to the service of God and His Church.

The reception of the tonsure implies the wearing of the clerical garb, or cassock. But the actual discipline with regard to the wearing of the cassock and the tonsure varies according to different countries, and is defined by the bishops of each province.

When his hair has been ceremonially cut by the bishop, the candidate is vested with the surplice, which is the choir dress common to all secular clergy. The surplice (superpelliceum) is thus called because it used to be put on in choir over the fur coat or fur-edged coat, which was worn during the winter months. The surplice is nothing else than an abbreviated and narrowed-down alb. The process of shortening the surplice gathered momentum from the fifteenth century onwards, until the manufacturers of church requisites produced the exiguous garment one sees in Italy. It is lawful to adorn with lace the edge of the surplice and its sleeves, but it is not difficult to see which of the two surplices is the more dignified — the abbreviated Roman cotta or the stately, lace-less Gothic surplice with its wide and long sleeves and ample folds.

The prayers, which accompany the rite of the tonsure, are an admirable explanation of the ceremony, as well as a most eloquent exposition of the mind of the Church regarding the dispositions, which she expects to find in those who seek to be enrolled in the ranks of her ministers. Canon Law distinguishes the clergy into two classes, the secular and the regular clergy — that is, those who live in the world, who are in charge of parishes and so forth, and those who live in community and are bound in some way or other by vows of religion. But, because one section of the clergy is called secular, it does not follow by any means that they may be satisfied with low standards and aims. The secular priest should ever bear in mind that the Church stresses, not the word secular, but the word priest. The regular clergy are the men who hold the trenches; the secular clergy are those who "go over the top." Both classes must be in perfect training — which, to drop the metaphor, means that without personal holiness no priest can hope to achieve much.

In the opening prayer the bishop asks that the candidate may receive the Holy Ghost precisely to guard his heart against the love of the world (a mundi impedimento ac saeculari desiderio cor ejus defendat). Whilst the tonsure is made, the new cleric protests that henceforth the Lord is the portion of his inheritance and of his cup, who will restore his inheritance to him.

Before vesting the candidate with the surplice the bishop recites a prayer, in which he calls it "the habit of holy religion" (habitum sacra religionis). This garment is the symbol of the new man whom he is to put on, who is made according to God in true righteousness and holiness. Its whiteness is the result of the fuller's labor, and it thus becomes a fit emblem of the constant need of renunciation and penance which are required if the cleric is to preserve unsullied the spotless purity of his soul.

The concluding prayer points out that, by the step he has taken, the cleric is bound to rid himself of all worldly habits and manners, even as he has stripped himself of worldly apparel (ab omni servitute saecularis habitus hunc famulum tuum emunda, ut dum ignominiam saecularis habitus deponit, tua semper in aevum gratia perfruatur).

We are here very far from the intention that at one time frequently prompted men, and mere callow youths, to receive the tonsure. They acted thus not from a desire to flee from the world or from a wish to pursue perfection, but merely from that of qualifying for ecclesiastical benefices which can only be legitimately held by ecclesiastics. In this way there was at one time, especially in France, a vast number of men who received the tonsure, though they had no intention whatever of ever proceeding to the higher orders. The impoverishment of the Church has had at least the advantage of removing from the ranks of the clergy those whose conduct was too often at variance with that which they had at least implicitly promised at the reception of the tonsure.

IV. The Minor Orders

The Sacrament of Orders consists of three degrees: the diaconate, the priesthood and the episcopate. In the episcopate the priesthood of Jesus Christ is fully unfolded, for, unlike the simple priest, the bishop is able to communicate to others of the fullness that resides in him. Hence, what we call the minor orders are in the nature of sacramentals, a preparation for the reception of the Sacrament towards which they point.

Door-Keepers Or Porters

In the primitive Church a man frequently remained all his life long in some one of these lower degrees which we now look upon as merely the preliminaries of the priesthood. Thus, a man would often remain in the office of "porter" as long as he lived. In the ages of persecution this office was a most responsible one, for it was the duty of the guardian of the door of the church to keep a lookout for the approach of danger and to warn the faithful within the building. In the exhortation which the bishop addresses to the aspirant, he enumerates the various duties of a door-keeper: they consist not merely in guarding the door of the sanctuary, but also in seeing to the safe-keeping of all that is found in the church. Hence, the porter was from the first the natural assistant of the deacon, who kept the treasury of the church. Later on the duty of calling the faithful to church by ringing the bell was added to the other duties of the door-keeper.

The Fourth Council of Carthage (fourth century) already mentions the form still in use at the ordination of the ostiarius. When the archdeacon has instructed the candidate as to the nature of his duties in the church, the bishop hands him the keys, saying from the altar: sic age quasi redditurus Deo rationem pro his rebus quae hisce clavibus recluduntur.

Nowadays the ordinary parish priest (especially he who is in sole charge of a church) is necessarily his own ostiarius; hence, it may not be impertinent to point out here that an occasional retrospective meditation on the minor order of the ostiariatus may be of great practical help. On that far-off day of our clerical career when we received this order, the bishop prayed that sit ei fidelissima cura in domo Dei, diebus ac noctibus. The church is the House of God. Surely it is no small matter, and not a trifling honor, to be appointed its guardian. The priest's spirit of faith will show itself in the neatness and seemliness of all the appointments of his church, and here there opens out to him a wide field for legitimate pride. A well-kept church (even if architecturally it has little to commend it) will yet be a "sermon in stones," and contribute no small part to the honor and glory of God. In this way the priest will render himself worthy of the reward prayed for by the bishop in the concluding prayer: inter electos tuos partem tuae mereatur habere mercedis.

Holy Orders- Part II

Holy Orders Part— III

This item 3625 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org