The MOST Theological Collection: Mary in Our Life

"Chapter XI: The Humility of His Handmaid"

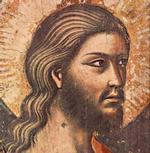

OUR LORD and His holy Mother could rightly claim to possess all virtues. Yet when He described Himself and proposed Himself as a model for our imitation, He mentioned the virtue of humility as especially characteristic of Himself. "Learn of me," He said, "because I am meek and humble of heart.1 Mary, too, as we have already seen in our consideration of the Annunciation, showed this virtue in an outstanding way.2 Indeed, at the very moment when she became the Mother of the Incarnate Word, she said, "Behold the slave girl of the Lord" (that is the precise translation of the Greek, as we have noted before).

In this chapter we shall talk about the virtue of humility. Exaggerated statements are often made in discussions of this virtue, but here, so that the reader may not feel the need of discounting the force of anything that will be said, let us agree to propose only statements that are strictly and literally true at their face value.

Let us understand at the outset that humility is by no means the greatest of the virtues; far greater are the three theological virtues: faith, hope, and especially love, which in itself sums up all. We must always keep before our eyes that the very essence of the spiritual life consists in charity-that is, love. But humility is necessary in order to make room for that love. It makes room by ridding us of extensive disorders of self. Now although we cannot, as it were, apply a measuring instrument to any virtue, and gauge it in degrees or any other mathematical unit, yet to help make the matter clear, let us use the following loose comparison: suppose I seem to have ten degrees of love. To make that safe, I ought to have ten degrees of humility. If I seem to have only five degrees of humility, then I must fear that at least five3 of the ten degrees of love that I seem to have are counterfeit. For love and humility rise and fall together.

What, then, is the special claim of humility on our attention? Its position is peculiar: though it is far from being the greatest of the virtues, it is a conditio sine qua non, a prerequisite for all other virtues. That is, if one does not have humility, he cannot really possess any other virtues at all. Of course he may seem to have many or all of them. But they will be counterfeits if they are not grounded on humility. St. Augustine very aptly compares humility to the foundation of a building: "First think about the foundation, humility.... the greater the structure will be, the deeper a man digs the foundation."4 The same St. Augustine gives another striking illustration. He proposes the question: Why was it that the Roman Empire grew so great? Basing his comments on the data of Roman history, he notices that the early Romans seemed to possess many virtues. They were satisfied with little for themselves: all was given to the service of the state. They showed prudence in their handling of conquered peoples, justice and mercy even to enemies, temperance in the management of public and private affairs, the greatest fortitude in war: an inspiring picture indeed. But, says St. Augustine, Divine Providence could not grant them a supernatural reward, Heaven, for these virtues. Why not? Because their works were not performed to gain such a reward. They were done because the people were

They sought only for praise: they received what they looked for. In the words of the Gospel, "they have received their reward."6

The same truth is taught in the Gospels in a forceful way. Our Lord is shown to us as marvelous in His mercy, in His love for sinners. Publicans who unjustly defrauded their own countrymen are treated kindly. A woman taken in adultery is most generously pardoned. In short, every kind of sinner meets with kindness and mercy at His hands-every kind, that is, but one. The only sinners for whom Our Lord seemed to have no mercy were the Pharisees. Yet they were to all appearances the most religious of men. They zealously kept the least prescriptions of the Old Law. They gave money to the poor. They fasted much. Yet to them Mercy Incarnate said:

The same thought is strongly expressed in the first Epistle of St. Peter: "God resisteth the proud, but to the humble he giveth grace."8 We note the sharp wording: it does not read, "God gives less grace to the proud," or "God gives no grace to the proud." God does not merely deprive the proud of grace. He resists them. If God Himself is against us, surely we are in a bad way. The only remedy is to turn from pride. For God retains mercy even for the proud in the sense that He is willing to cure them of their pride if they will accept His help.

Why is this virtue so dear to Christ and His Mother? It is because it makes room for God. If the essence of spirituality lies in love, love of God, then it follows that we must make room in ourselves for God. Now that room is made only at the expense of the disorderly self in us. The virtue that digs the foundations and makes room is humility. Conversely, the opposite vice-pride-is implicit in every sin. Pride attempts to claim for a creature what is really due to God. Hence pride, as it were, aims at dethroning God and setting up a creature-self-in His place. No wonder pride is so odious to God!

Humility is the virtue that teaches us to know our true place in the scheme of all things, and makes us willingly accept that place. Hence humility is based on truth. Thus it becomes apparent how it was possible for Christ and His Mother to be humble. Insofar as He is God, Christ is the Lord of all. Yet He freely wished to assume human nature. And He did not merely assume human nature, but became a member of a fallen race (though He Himself did not have a fallen nature). Having once made this choice, He would not recoil from the consequences thereof: He willingly accepted the hardships and difficulties that are the lot of a fallen race.9 But He did not accuse Himself of sin: to do so would have been contrary to truth, and humility is founded on truth, the true estimate of one's proper position.

Now it is all too easy to misunderstand the notion that humility requires us to recognize our true position and accept it. Many of us will promptly throw out our chests and say: Yes, I am good, and I really ought to admit it Such a statement is based on an untrue and incomplete view of our position. To counteract such a danger, we ought to review briefly just what is the truth about ourselves.10

We must recognize at the outset that we are creatures. In us there is good and evil. (Of course evil is not a positive thing: rather it is a lack of the good that ought to be there.) We must determine what in us is due to ourselves, and what is a gift of God. Let us begin with the natural order. First of all, we were made out of nothing by God. Therefore, of our initial equipment there is nothing that we have not received as a completely unmerited gift: how could we merit anything when we were as yet nothing? Hence, as regards the starting point, we have nothing of ourselves, everything from God. But now that we have begun to exist and live, what shall we say? The very same metaphysical principles that require the work of an Infinite Being, God, to bring us out of nothing require the unending work of that same God to keep us in existence, and to enable us to perform any action, however small. (Recall that we are at present speaking of the natural order.) But can we at least choose to do good or evil? Yes, we can, for God has given us free will-but we need His support even in the use of our free will, insofar as there is any good in it. As for the evil, we must attribute that to ourselves.

In order to grasp more clearly what is God's role and what is our role in a choice or action, let us take a crude example. Consider the act of picking up a roll of money from a table. One man, the owner, may perform the act, in which case it is a good act in every respect. But suppose a thief performs the same act: we hen have a sinful act. For something is lacking when the thief performs it. It is the same physical action as when the owner did it, but the thief lacks a right to the money. But is the act of the thief evil in every respect? It is surely evil in the moral order; but it is not evil in the physical order.11 Though the act is evil morally, it has a sort of physical goodness and that physical goodness as a good requires the support of God. But the moral evil which is a lack of a required quality belongs to man. In a good action, however, both the physical and the moral goodness require the support of God. Therefore, we may say that we are able to lack something without God, but are not able to be or to do anything without Him.12

Thus we see that what we can do of ourselves is extremely little. Yet, although our co-operation with God in producing any good action is so pitiably slight, God requires it of us under pain of sin, and rewards it richly when it is given.

We have found that we can be nothing and do nothing without God. But we can lack something-i.e., we can have evil will-without Him. We can now understand the sense in which some of the saints have said of themselves: "I am nothing, I can do nothing, I am less than nothing." Now one cannot really be less than nothing. What they mean is this: they could do no good without God, but they could be lacking in something without Him. In that sense, seeing their capacity for evil but not for good, they realized that they were less than nothing-for to commit sin is worse than to do nothing.

We have had a glimpse of the shattering sight of our position in the natural order. Much meditation is needed to bring it home to ourselves. We need to do more than just look at the truth; we need, with the help of grace, to realize it and act upon it. It is a long task to make the same examination in the supernatural order (The Path of Humility may be a help in the task). But we can easily conclude that if we are so poor and helpless of ourselves even in the natural order, the same things must be even more true in the supernatural order. Hence Our Lord Himself told us: "Without me you can do nothing."13

Thus far we have considered only our capacity for sin. When we realize that we really have sinned, and that we have sunk still lower because of having sinned over and over again, what shall we say of our position? Surely it is not one to feel proud of. No wonder the saints could consider themselves worse than nothing For by the realization that of ourselves we have a capacity for evil, but not for good, we can come to lack esteem for ourselves. When we add to the picture the fact that we have sinned, we can honestly have contempt for ourselves. We can justly call ourselves "unprofitable servants."14 In fact, we easily become worse than unprofitable, for by our intractability and lack of docility we often hinder God's designs.

But yet we must not forget that there are two elements in us: that which we have from God, and that which we have of ourselves. Looking at the latter, we can properly arrive at contempt of self But looking at our dignity as sons of God, as sharers in the divine nature through grace, and considering what we can do with the divine help, we can still conceive a proper kind of self-esteem. The right sort of humility agrees well with magnanimity, the virtue that makes a man dare to undertake great things for God and neighbor, relying not on self, but on the divine power. In this sense St. Paul says, "I can do all things in him who strengtheneth me."15

We have considered thus far what humility ought to be in relation to God; we see that it is founded on an attitude of truth, on reverence toward God, as well as on knowledge of our own nothingness. We must now consider what humility should be in relation to other human beings. Here the truth is more difficult to see. How can we honestly, without self-deception, follow the advice of St. Paul: " ... in humility let each esteem others better than himself ... "?16 Many confusing things have been written on this point, as if St. Paul wished us all to deceive ourselves.

For it is obvious that out of all men, only one can be the worst sinner in the strict sense of that term. All others are somewhat less bad. St. Paul is not demanding that each of us think himself the very worst sinner in the world.

St. Thomas Aquinas gives us the true solution.17 He tells us to distinguish two things in us, as we have already done above: what we have from God, and what we have of ourselves. We can then make three comparisons: 1. If we compare what we have of ourselves to the gifts of God in others, we can and should, out of reverence for the gifts of God, defer to others, esteeming them in this way better than ourselves; 2. But if we compare the gifts that we have from God to those that others have from God, humility does not demand that we think our gifts less, since they may actually be either greater or lesser: humility demands only that we give the credit to God, not to ourselves, if they are greater in us; 3. Similarly, if we compare what we have of ourselves to the fame element in others, we are not obliged to consider ourselves inferior to all-otherwise each would have to consider himself the greatest sinner, which is, of course, mathematically impossible, for only one can claim that dubious title. But, St. Thomas adds, we ought nonetheless to be inclined to conjecture that others have some good in them which we do not have, or lack evil that we know we have.

If we wish to be scrupulously exact on this last point we shall have to admit that we simply cannot make an accurate comparison between ourselves and others. We can, it is true, see their external acts. Thus I may see a robber who has also murdered six men; inasmuch as I have not done those external acts, I seem to have a better record. External acts are important But even more important is the state of a man's soul. Was he fully responsible? What would he do if he had had the graces that we have had? To make an accurate comparison between ourselves and others we ought to have precise knowledge of two things: Our own state of soul, relative to the graces we have received; and the state of soul of others, relative to the graces they have received. Now our own self-knowledge is but imperfect at best; and our knowledge of the interior state of others is even dimmer -it is all but total darkness. Hence we really cannot make an accurate comparison of our own spiritual worth with that of others. Yet, without dishonesty, which must be avoided with the greatest care, if we have a true knowledge and appreciation of our own weakness and failings, we can in all truth say: "If that robber had received the graces I have had, I wonder if he would not be much better spiritually than I am. It is hard to see how he could have done much worse than I, with such graces as I have been given." St. Francis of Assisi actually did say this sort of thing, and was honest in saying it.18

If we wish to understand the great lengths to which some of the saints go in humility, we must consider the motives that impel them. First of all, they love humility because Jesus and Mary love it If we really love anyone, we want to be like them. They meditate much on the humiliations of Bethlehem, of Calvary, and on the continued humiliation of Our Lord in the Holy Eucharist, in which He takes the appearance of a lifeless thing, at the mercy of anyone who handles the Sacred Species. Next, they have a powerful and quite wholesome fear of illusions and self-deception. They see in humility, which is based on truth, an excellent protection against being ruined by any deceptions. And when we see the saints rejoicing to receive even obviously undeserved humiliations and insults, they are using yet another method in addition to the desire to be like Jesus and Mary and other motives already suggested. They can always reflect: It is true that this insult, in the present circumstances, is something I do not deserve. Still, when I consider what my past sins have deserved, the punishment I ought to have had for offending God but have not received, here is a fine chance to take this as a payment for the past, to make reparation to the Heart of Christ for the pain19 that I have caused Him.20 In addition, they realize that humiliations inflicted by others provide them with a chance for much greater spiritual progress in a short time than many a self-imposed humiliation. And, finally, they wish thereby to earn graces for others.

Is it correct to say, "As soon as we think ourselves humble, we cease to be so in reality"? Some writers maintain that one who is humble cannot know that fact. It is difficult to agree with that view; it seems to suppose that humility is founded, not on truth, but on self-deception (although it is true, as we shall see, that humble persons tend to be suspicious of their own humility). We may approach the matter in this way. There are many degrees of humility. A complete absence of humility would mean that we would have formal contempt for the authority of God as such. We wonder if any one but the devil himself could reach such a depth. Perfect humility is that of Our Lord Himself. The truth about any one of us probably lies somewhere in between. A man may honestly think to himself, or say to his spiritual director, "I think I have some humility, not perfect humility, but some low degree, less than I ought to have." It is easy to see that our degree of humility is low: if it were high, we would be making wonderfully rapid spiritual progress. But, unless acting under a special divine inspiration, a man would probably be guilty of pride, and would surely seem ridiculous, if he were to proclaim to others: "I am humble." He would be in danger of being "proud of his humility." Yet the fact that we know within ourselves that we have some humility does not of itself destroy humility; Our Lord was humble, and admitted it; so was Mary, and she knew it.21

Humility is primarily a great gift of God, for which we must pray much, and St. Thomas says, "They who share in the gifts of God know that they have them."22 But we must concede that the theologians who disagree do have a certain truth in mind, for humility is a delicate, elusive virtue. There is danger that we may indulge in a self-deceiving pride in even a lowly appraisal of ourselves and our little humility. St. Teresa of Avila gives us the wholesome advice that we ought to be suspicious of the genuineness of solid virtues that we seem to possess:

But I advise you once more, even if you think you possess it, to suspect that you may be mistaken; for the person who is truly humble is always doubtful about his own virtues; very often they seem more genuine and of greater worth when he sees them in his neighbours.23

St. Teresa is not urging us on to self-deception: it is merely being realistic for us to suspect the degree of our humility. We can know, of course, that we do not have the formal contempt of God's authority of which we spoke; but whether we have much more than a bare minimum of humility is another question. For pride is able to counterfeit all virtues. And it can even contrive an appearance of humility. In our best actions, often a part of our motive is apt to be a secret desire for self-esteem or for the esteem of others though we do not realize it We must learn to suspect the presence of such hidden pride and to seek it out. In suspecting that some of our humility may be only apparent, not solid, we are taking a precaution against self-deception, not indulging in self-deception. Therefore we must pray to God that even the little humility we possess may be real, not illusory.

Humility should incline us to wish to avoid even deserved praise. For praise is a danger to humility even if the praise is well earned-not that truth is dangerous of itself, but because of our normal human weakness. We may and should recognize the gifts that God has given us, but we must be careful not to take to ourselves the credit for them. If we keep in mind the explanations given above on what part is due to us, this becomes possible, though not easy.

While humility is difficult to acquire, a deep realization of our own nothingness and of the infinite greatness of God will help us develop it. But a speculative knowledge of these truths is not enough; they must be impressed deeply by much meditation. In our meditation we should also dwell long and lovingly on the humility of Our Lord and His blessed Mother. It is likewise good to think often on our past sins, but observing this caution-that we do not recall certain types of sins so vividly as to cause new temptations. Our outward actions should be such as the virtue of humility suggests, but, in general, unless we have a special inspiration of grace, it is better to be content merely to avoid, so far as we can, any singularity that attracts attention to ourselves. If humiliations from others come our way, however, it is most helpful to accept them.24

Prompt obedience to all lawful authority is an excellent means of growing in humility. For there is a close relation between obedience and humility: both serve to make us empty of self, and it is the function of humility to make room for love by ridding us of disordered self. Now when we obey, we also contradict self, for we are following the directives of someone else-not our own wishes. Hence we can see the great value of obedience, even when a superior gives us an order to do something that is less good and prudent than it might be. The superior may err in his judgment, for he is only human, but we, in obeying, do not err, for we thereby substitute the will of God for our own disordered self (assuming, of course, that the command is not to do something sinful). This is the reason the saints disliked accepting posts of authority: it is much safer to obey. The truly humble man will not only obey, but he will make an honest effort, so far as he reasonably can, to see things the superior's way. This is obedience of the judgment.25 For he will recall that his own judgment is very apt to be warped in things that concern him; and, in addition, he recognizes that the superior has better access to the facts, and possesses graces of state.

As to speaking in a lowly way of ourselves, a certain caution is needed. St. Francis de Sales warns us not to do this unless we sincerely mean it,26 as it could easily happen that we might really be seeking praise through what would seem to be humble words. We should make it a practice to speak as little as possible of ourselves, as this danger is unlikely to occur in silence about ourselves. A tendency to criticize or dispute much is often rooted in pride. Hence we do well to avoid such activities unless they are really necessary. Finally, we must constantly beg God for humility, for humility is, like all other good things, basically a gift of God.

And now a brief look at the relation of humility to the grace of final perseverance-for it is obvious that unless we persevere to the end, it will do us no good to have received all other graces. We might express our situation in this way: On what do we pin our hope that we will actually avoid grave sin and persevere so as to be in the state of grace at the end? If we attempt to rest that hope on our own ability and constancy, we are building on sand, for we are notoriously inconstant in good-and this is true of the best. We must, then, depend on God for this great grace-that is, we must depend on Him to send us such graces as will effectively insure that we will co-operate with grace without, of course, taking away our free will. How shall we obtain this great grace from Him? We cannot merit it: Scripture and Tradition offer us no text in which God has promised us the means of meriting it. But we can obtain it by constant humble prayer. For although we do not have the means of meriting it, we can still ask for it. As in the case of all other graces, it is through the hands of Mary that we must obtain it. To her we say many times daily: "Pray for us, now and at the hour of our death." A close attachment to her gives us solid reason for confidence that we will be given that all-important grace.

Thus humility leads us to take the attitude of little children toward God our Father and Mary our Mother. Let us recall that, as Our Lord said, if we do not become as little children, we shall not get into Heaven at all. Now a child expects to receive things from its mother, not because he, the child, is good. No, the mother, though she rewards the child for the good he does, yet gives most things to the child not because he is good, but because she is good. Similarly, though we are capable of earning, thanks to the gifts of God, certain graces, yet even the means of earning them has been freely given to us. In this sense we may say that our chief contribution is to refrain from being bad children. God gives us good things through our Mother not so much because we are good, but because He is good. And the reason Mary can serve as the channel of all graces is that she is completely empty of self: Ecce ancilla Domini!