The Comforter of the Afflicted

by Zsolt Aradi

Transylvania is one of those small areas of Central Europe, which clearly displays through its very continuity of existence the ageless struggle between European West and European East. The country has suffered some wounds as well as gaining great benefits from Central Asiatic influences. Transylvania for many hundreds of years was part of Hungary. Then it became independent, ruled by Hungarian princes who nevertheless considered themselves Transylvanian rather than Hungarian. After World War I, the country was joined to Romania, then parts of it were returned to Hungary; and when World War II ended, the country found itself once more under Romanian rule.

Today its population is more than half Romanian; the next largest group is Hungarian, while the third determining cultural and folk element is German-Saxon; it is a place where East and West really meet. The Germans began to settle there in the twelfth century and some, mostly Lutherans, remain there now. The Hungarians occupied it in the ninth century; and the Romanians, who came up from the South and Southeast through the Carpathian Mountains, still proudly cherish their Latin tradition derived from the Roman Empire.

The history of these three peoples is filled with grand tradition, including events of world importance. The Hungarians were the unchallenged rulers of the area from the beginning. There are beautiful legends that some parts of the Hungarian population, so-called Seklers, are actually remnants of Attila's Huns who, when they were driven from Europe in the sixth century, were led there by his son Csaba. This heir of Attila disappeared from history in the shadows of the legends, though fairy tales relate that he rode up into the Milky Way, which the Seklers still call "Road of Csaba." The Romanians, among the most ancient inhabitants of the Balkans, were Romanized by the Roman legions who occupied this territory. Emperor Trajan is considered one of the great forefathers of the Romanians; their language is a romance language. The Saxons were brought in by the Transylvania Princes to become traders and by the religious to be missionaries, and afterwards they generally followed the pattern of the German march to the East. The Romanians later fell completely under the influence of Byzantium; they followed the eastern schism and their Catholics were of Eastern rite. The majority of the Hungarians are Roman Catholics and the rest are mainly Calvinists. All three peoples were subjected--the Romanians most of all--to Turkish domination. Romania, beyond the Carpathians, regained her independence at the end of the nineteenth century after four hundred years of Moslem rule.

In spite of their different cultural traditions, these three peoples were united in two important respects. They looked to the West and considered themselves its easternmost defenders. Secondly, they always thought of themselves first of all as Transylvanians. Sometimes they fought each other, but peace soon descended as soon as they found renewed brotherhood in their mutual love for this extraordinary little country.

It is not without significance that the first decree of religious tolerance in Europe was signed between the Transylvanian nations and their respective religions in the seventeenth century. And though one of the great Princes of Transylvania, Gabriel Bethlen, was a powerful ally of Gustavus Adolphus, the leader of the Protestant forces in the Thirty Years' War, it is related that he had such a sense of tolerance that he once donated a statue of the Madonna to a Catholic community.

The rather extraordinary influence of Transylvania can be traced through the centuries in Hungary, Romania, and Moldavia, in the neighboring Central and Southeast countries and in the court of the Sultans in Constantinople. This small territory is dotted with medieval memories. There are ruins of cathedrals, of churches, many shrines of Our Lady, places where people gathered together to await the marauding Tartars or Turks.

Shortly after the Christianization of this area, the greatest friends of these various people were the Franciscans and the Minorites; it is of deep significance that the Franciscans have been called from those early days to the present, not "Fathers," but "Friends." Their identification with the people whose misfortunes and happiness they shared has shown them to be truly "friends."

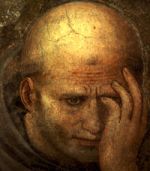

The Madonna of Csiksomlyo-Sumuleu belongs to that territory of Transylvania where the Hungarian Seklers live. The foundation of the Franciscan settlement and the church itself date back to the fourteenth century. There is some dispute concerning the carved wood statue itself. Some claim that is a work of the Sekler folk people; others assert that it is an original carving by Veit Stoss, the great German sculptor of the sixteenth century who traveled in Transylvania; still others say that the Franciscans, driven out by the Turks from the Romanian plains, brought it along and that it is thus distinctly Romanian. The fact is that the Seklers consider it their own, and though venerated by people from all nations, it has become part of the cult of the Catholics of the Latin rite.

The statue of Our Lady of Csiksomlyo is clearly a peasant Madonna. Her round face shows the characteristics of the Southeast European racial mixture. Like the Madonna and her shrines in this and other territories of Eastern Europe, she was primarily the refuge of Christians in their tremendous adversities. The Sekler folk, who have the most colorful folklore in every respect--literature, dress and forms of religiosity--in order to show their gratitude for the miracles and help, built her a sumptuous Gothic cathedral, which was later rebuilt in Baroque style. But church and shrine have distinct Byzantine characteristics as well. From their establishment in the fifteenth century, the shrine and church were open to all nations. Documents prove that the statue was considered a worker of miracles as far back as the middle of the sixteenth century.

The monastery and the shrine were attacked many times. A Tartar officer attempted to pierce the statue with his lance. Surrounding buildings burned down six times, but the statue remained untouched. The invading Tartars once were driven back by a small force of women dressed in soldier uniforms. The people, harassed by civil and foreign wars, despoiled by the invaders and by their own lords, very often felt themselves entirely helpless and ran for aid to the shrines of Mary, and if at all possible, first to the sanctuary of Csiksomlyo-Sumuleu.

The challenge of Western and Eastern ideas was felt here, yet somehow in this hallowed spot, the conflict seemed to lose its bitterness. The simple, crystal-clear faith, like the surrounding mountains, remained strangely unchanged. The small chapel and settlement of the Franciscans were replaced by a larger church joined to some other chapels; this veneration reached such intensity that this shrine, unknown by the Western world, finally became a Basilica.

This item 3053 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org