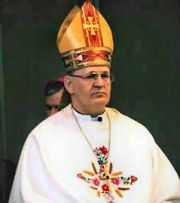

Cardinal Peter Erdo on the Church in Hungary

Q: After the difficult years of totalitarianism and the silent sacrifice of many religious and lay people, the Catholic Church in Hungary has greater freedom of expression and of evangelization. What are the present difficulties and the future hopes?

Cardinal Erdo: Above all, to be able to address the present difficulties there must be some reflection on the difficult years of totalitarianism. At the end of the Socialist era, the gravest problems certainly did not come from an open and direct persecution.

Cardinal Erdo: Above all, to be able to address the present difficulties there must be some reflection on the difficult years of totalitarianism. At the end of the Socialist era, the gravest problems certainly did not come from an open and direct persecution.

A certain oppression existed; already present at that time was a "deformation" of society and people's mentality. I am referring above all to so-called goulash Communism, famous during the last years of Janos Kadar's regime. Its effect was to turn people too much toward individualism, concentrating all their attention on personal well-being — at times mere futilities — and accustoming them to short-term reasoning without thinking about the "greater future," having lost their great ideals.

This petit-bourgeois egoism very much checked the enthusiasm and idealism of society. This type of "transformation" or "deformation" is still present in the society. It is not easy to free oneself from this weight, or the problems, for example, caused by juridical limitations.

Abortion is still very high in our society and the birthrate is the lowest in the whole of Europe. Every year we lose 40,000 inhabitants that, for a country of 10 million souls, is not a small loss.

What is lacking, therefore, is future vision; there is a lack of all types of "ideality" and also, for this reason, sensitivity for religion is quite scarce.

From such a context arose our "institutional freedom," but the state, whose competence it is, can, in the first place, change the institutional conditions. Perhaps only within a decade will there be — as a consequence of these social modifications — a psychological and moral change: a change of attitude in the society.

Contrasted with the great freedom, the great change, certainly present and important, is the still grave weight of the general mentality to which are added the problems that are typical of the West, characterized by a profound secularism. Institutional development has certainly been spectacular in the last 15 years, especially in regard to schools, residences, and social and charitable institutions.

Q: In what way does the Church try to keep alive its philosophical and moral tradition in cultural institutions — primary and secondary schools, universities, formation centers — and in those sectors of society that are more sensitive to the reception of and listening to religious teaching?

Cardinal Erdo: Religion is not a curricular subject in schools in Hungary. Classes are imparted in the school building, but with a very clear separation from the rest of the subjects. Such teaching reaches almost 25-30%, while presence at Sunday Mass reaches 10-12% of Catholics.

Therefore, it is clear that the teaching of religion in schools is in a "missionary situation." Sadly, the results are not encouraging. Among those youths who have received such education, only very few then find the path to the Church, to the parish community, to Sunday Mass and to the sacraments.

So we must ask ourselves how we can improve this teaching, also at the human level, without neglecting, on the other hand, the content. This "general depression" does not only characterize our society but the whole of the West, where the lack of clear ideas is obvious and one notes a "cultural ruin," to the point that even believers do not know their faith in-depth.

Also, young adults and adolescents — I am referring, of course, to those who frequent the Church — not rarely have "strange things" in their heads. Therefore, it is extremely important that the teaching of religion have clear contents and be able to present all the richness of our faith, not just some partial points.

We must not be content with the transmission of several positive sentiments of humanity, of fraternity or of religiosity in general, but must transmit the content of the faith.

Q: There is in Hungary a rich presence of religious and secular institutes, as well as of congregations committed in several pastoral environments. What space do the new ecclesial movements have at present and how are they approached?

Cardinal Erdo: There are, and were of course, movements of spirituality above all from the West, from the Latin world, especially from France, Italy and Spain, which are quite active. But they do not have the same success they have had in some countries, such as the Slav countries around us — perhaps because our society is very tired or, perhaps, because there is much hesitation to commit oneself in the movements.

As many young people are afraid of an existential choice — marriage at the appropriate time, a profession, a priestly or religious vocation — so they are also afraid of commitment in the framework of a movement. Therefore, there are many sympathizers and relatively few who are really committed.

Q: Not long after the joyful images of Cologne's World Youth Day, in which thousands of young people from all over the world took part, what is the relationship between the Church and young people in Hungary? In what way do they approach religious practice and ecclesial commitment?

Cardinal Erdo: I have responded in part in the previous question, but I might add that obviously in all our dioceses there are specialized sections for work with youth. It is not cultural but pastoral work: Both catechesis as well as matrimonial or pre-matrimonial pastoral care have an important role.

There are, moreover, youth groups, as well as diocesan, regional and national meetings. I like to mention, for example, the Nagymaros meeting, which for decades has assumed a distinctive character in the Hungarian context. There are, in addition, pilgrimages for young people which at present are beginning to be somewhat "fashionable."

Catholic schools and, of course, the Catholic university offer the appropriate institutional framework for meetings and dialogue with young people. But even here, it is necessary to reflect more profoundly on how much we have done to date for the greater efficacy of these meetings.

Among the students and pupils, how many are there who have found the path of religious life? Of course, in the university and in the different schools there are chapels where Mass is celebrated and liturgical and pastoral programs are carried out. But it is not at all easy to measure the efficacy of these things.

We must be optimists! We must meet the parents and relatives of young people to offer a new path to the whole family. It is not easy to find the suitable instruments, but there is great commitment.

At the level of the episcopal conference, there is a bishop who is responsible for work with youth and there are trained teams for the organization of this type of work, who committed themselves intensely to Cologne's WYD.

Those who returned from Cologne are all enthusiastic, despite the inconveniences. They were impressed by the catecheses they received, the meeting with the Holy Father, the liturgy and, finally, the personal cordiality of the Germans. This openness of the believers of Germany was a surprise for our young people.

Q: Young people in Europe who want to follow a vocation are faced with the obstacles of secularization and the trend away from making responsible and lasting choices, but are helped by the strong presence of new charisms and ecclesial communities. What is the situation like in Hungary in particular?

Cardinal Erdo: Hungary, of course, is also in need of vocations. Perhaps this lack is not as dramatic as in some Western countries, but it is quite acute above all because in the last 50 years religious vocations were not accepted, it was not allowed to live a religious life.

For this reason, whole generations of priests and religious are missing; and although the proportion of seminarians is higher than in German-speaking countries, the proportion between faithful and priests is worse. For example, in our archdiocese, for each priest we have 6,000 faithful, which is far worse than the European average.

In these last years the seminaries have had a certain stability as regards the number of students. There has been an effort, lately, to reform the educational system somewhat to reinforce the vocation of those hesitant young men who enter the seminary without having made a definitive decision. On this point I should say that it is above all a problem of the anthropological foundation for this choice.

Q: Relativism conditions every aspect of personal, social and cultural life. The negative consequences are clearly visible, in a special way in the disintegration of the family, which, according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, is the "domestic Church," the first cell of society. Given your pastoral and juridical experience, how can the Church check such a tendency?

Cardinal Erdo: Our humble experience, which derives from the "profound Communism" of the '50s and '60s, shows that — although the great institutional solutions at times might seem spectacular and decisive — true strength is found in far more modest communities, such as the parish community, the community of several families with many children who help one another mutually.

This existential help is of course also financial, but above all personal and direct, as in the case of personal assistance to young mothers who have small children and are not able to leave the apartments in which they live.

This "direct help" is really precious. Also the Church — despite the difficulties and the complicated organization due to so many of society's needs — has understood perfectly that this type of "direct relations" is stronger because it goes beyond the public circumstances of a state and a society, which change frequently. These models are transmitted psychologically also to future generations.

I can talk about my personal experience. My parents had a large family. At the beginning of the '50s there were six of us siblings at home, and we were surrounded by about a dozen other Catholic families, and we helped one another mutually. Very often the children of these families have in turn had numerous families, and I have had the job of welcoming some of these grandsons to our seminary.

Q: Hungary is characterized by an historic multi-confessional presence, to the degree that it can be considered as a kaleidoscope of the new Europe. What have been the results of this secular experience in coexistence and the ecumenical and interreligious dialogue?

Cardinal Erdo: First of all, Hungary is a small country, very open to all influences coming from abroad. The country is very exposed to the interplay of the world's and the continent's powers.

So let's have no illusions about being able to take decisive steps, for the whole world, not even in this area. Our experience is therefore limited to our circumstances, which, however, can also express values that are important generally.

Tolerance and especially empathy toward other confessions is something of notable value. In the center of everything must be "historic reconciliation," because the past has left us profound wounds.

We must speak of it without rancor or prejudices, seeking to tell our history again in a "reconciled" way, self-critical but always truthful and faithful to the historic truth, so that a basis may be found for a common discourse in fruitful collaboration in present-day society.

Of course, Hungary is a place that lends itself much to dialogue, both with Protestants as well as Orthodox, even though being less numerous, and also with Judaism.

Q: According to the principle of subsidiarity, often asserted in the social doctrine of the Church, the main institutions and intermediary bodies must collaborate actively, having as their ultimate end the common good. What are, in this connection, the present relations between the state and Church in Hungary?

Cardinal Erdo: First, all models have value when in the society there is at least a smidgen of correctness. When a state is a state of law then, of course, it is necessary to observe the laws.

This model is a model that has shown its merits in the Western world and we are struggling for this legality of a Western type, for the functioning of this new democracy.

In any case, in every country of our region we see profound problems because we have had to assume in very brief time institutional forms irrespective of our social reality.

Therefore, the juridical and institutional forms are not organic products of our social reality, but "gifts" from the West that we have accepted with joy because we appreciate the general values that are behind these democratic forms.

Of course, a rather long period of suffering is necessary for these forms to be able to reflect a reality that is truly respectful of the person, of justice, etc.

Therefore, yes to subsidiarity but not only a subsidiarity of mere institutional forms, but rather an "organic subsidiarity" in the reality of the society — which is a much longer task, as in the case of the changes in property relations. Of course, Communism had expropriated all the goods of society and, consequently, after Communism a new class was born. But in what way?

This is not at all clear for the majority of the society, to the point that some debate or doubt the legitimacy of large private properties born in the last years. So this is also a moral weight. We must make an effort, on this point, to understand how society can find its balance, both moral as well as institutional.

Perhaps the West's democratic institutions can help us in this development. But it is even more necessary for us to have Christian generosity and confidence in providence and in divine mercy.

This item 6651 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org