Make your gift today!

Help keep Catholics around the world educated and informed.

Already donated? Log in to stop seeing these donation pop-ups.

Abridging Herman Melville’s faith, and perhaps our own

By Dr. Jeff Mirus ( bio - articles - email ) | Mar 13, 2017

There are benefits to giving up reading mysteries for Lent. For one thing, I finally finished a project that both Phil Lawler and Thomas Van recommended when they learned that I had never gotten around to reading Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. That was a Catholic gap I was loath to admit, until Phil started nattering on about “the Rex Mottram approach to Amoris Laetitia” back in November, and I had to look up the reference.

Since then I’ve learned to admire Waugh’s delicately moving tale of faith lost and recovered by landed gentry in England, as they were rapidly displaced during two world wars and the time between. I was also astonished by Waugh’s sheer brilliance as a writer. It ought to be clear by now that I haven’t read everyone, but Evelyn Waugh must nonetheless be one of the finest prose stylists who ever put English sentences on a page.

For all that, the privilege of becoming today’s topic belongs rather to my second Lenten foray into real literature for 2017, namely Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. I was already familiar with this long book having read it in American Literature during my junior year of high school. At the age of 16 (and a male, to boot), I was largely insensible to Melville’s deeper psychological and spiritual currents but, unlike many of the sixteen-year-old girls, I found fascinating his detailed descriptions of whaling, including the methods for removing blubber from the whale’s carcass. Some of the images of the process, with men working inside that enormous body, remain in my imagination after more than fifty years.

I knew by the time I entered college that there were strong (but not decisive) arguments against reading outstanding works of any kind at too young an age, just as there are strong (but not decisive) arguments against ready anything worthwhile as a school assignment. Both the student’s age and inclinations almost invariably ensure that the best things will not be thoroughly understood. It is likely that the works in question will be vastly under-appreciated and even actively disliked. Finally, the labor will often trigger a signally unfortunate attitude: “Well, at least I won’t have to read that book again!”

I have long considered it a grace to realize I should read Moby Dick again, and another grace that I had at least a moderate desire to do so. Exactly fifty-three years later, I have finally begun.

I launched this second voyage through what is typically called “the great American novel” by taking up the copy we had on our shelves, a 1931 edition which I believe my wife inherited from her parents. My own small paperback version from high school had long since disappeared. But although this edition is not described as abridged, when I read the somewhat rhapsodic introduction by one William McFee, I noticed a final paragraph which was so rapidly and casually expressed as to read suspiciously like a cover-up:

Melville, indeed, abandons his entire story at times to plunge into the history and literature of whaling. A few such digressions have been omitted, as have also the mythological and Biblical discursions later on in the book. But the immortal spirit of Melville’s masterpiece, the music and rhythms of his prose, have been preserved.

Perhaps this makes a little bit of sense if one is reading Melville as a teenaged boy. But I began to wonder what I might be missing without being told, especially since I guessed the “Biblical discursions” would interest me enormously. These, surely, would also provide considerable insight into Melville’s own worldview, along with that of many of the whalers he described.

The First Lesson

Remembering my Kindle after reading about fifty pages, I went online and downloaded the complete works of Herman Melville for the beggarly sum of two dollars and ninety-five cents. I then started over, skimming from the beginning. At least as early as the sixth chapter of the 134 which make up the original work, I noticed significant passages that were not present in the 1931 edition, and then I saw that this edition’s chapter 4 was already an abridgement of chapters 6 and 7 in the original. So much for the emphasis on removing discursions which came only “later on in the book”!

The first critical missing piece was in the description of the main character’s entry into a small chapel in New Bedford which served seaman and their widows. You will remember that Moby Dick begins with one of the most memorable lines in all of literature: “Call me Ishmael.” In fact it was this very Ishmael who reflected on the many memorials to dead seamen which adorned the chapel and its property. It is also the voice of this same Ishmael in which the entire story of Ahab and the great white whale is told. How can it be, then, that the editors found Ishmael’s reflections on the death of whalers so thoroughly unnecessary, when he was whiling away the hours between his arrival in New Bedford and his opportunity to take ship on a new whaling expedition of his own?

Clearly we must not be cheated of such timely wondering. We must have Ishmael’s hopes and fears in full:

It needs scarcely to be told with what feelings, on the eve of a Nantucket voyage, I regarded those marble tablets, and by the murky light of that darkened, doleful day read the fate of the whalemen who had gone before me. Yes, Ishmael, the same fate may be thine. But somehow I grew merry again. Delightful inducements to embark, fine chance for promotion, it seems—aye, a stove boat will make me an immortal by brevet. Yes, there is death in this business of whaling—a speechlessly quick chaotic bundling of a man into Eternity. But what then? Methinks we have hugely mistaken this matter of Life and Death. Methinks that what they call my shadow here on earth is my true substance. Methinks that in looking at things spiritual, we are too much like oysters observing the sun through the water, and thinking that thick water the thinnest of air. Methinks my body is but the lees of my better being. In fact take my body who will, take it I say, it is not me. And therefore three cheers for Nantucket; and come a stove boat and stove body when they will, for stave my soul, Jove himself cannot.

This may not be perfect theology. Especially in our own day, we must not too quickly dismiss the body as “not me”. But these words capture the very spirit of mortal adventure. They reveal something very deep in Moby Dick’s main character, and almost certainly something deep in a remarkable author who was so very skilled at capturing the essence of human life.

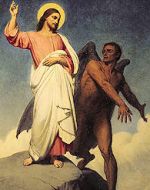

We must beware, then, of abridgements, and perhaps especially in Lent, lest we pass over even the crucifixion of Melville’s savior far too quickly. We must slow down and savor the meaning of the entire tapestry of words. For if this initial statement of Ishmael’s faith can be so easily discarded as extraneous to a dramatic tale of life and death, what can possibly qualify for inclusion? What, in the end, can matter more?

All comments are moderated. To lighten our editing burden, only current donors are allowed to Sound Off. If you are a current donor, log in to see the comment form; otherwise please support our work, and Sound Off!

-

Posted by: billG -

Mar. 14, 2017 7:09 PM ET USA

May I recommend to you the Nortwestern-Newberry edition of Moby Dick. The book is so full of allusions that most of us, due to poor education, no longer understand. The edition in question is replete with footnotes that explain what otherwise would just raise our eyebrow. And I suspect you will find much substance for future comment in the chapter called the Try Works.

-

Posted by: jackbene3651 -

Mar. 13, 2017 10:37 PM ET USA

Anyone interested in Melville's work should be sure not to miss the short story Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street.